(By Mohsin Tanveer)

Oct 10, 2025

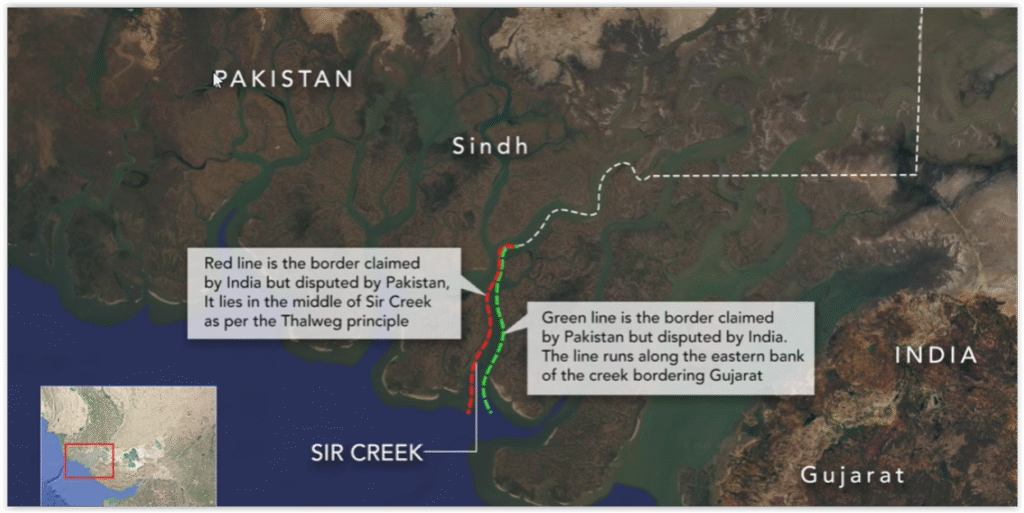

Sir Creek dispute as one of the most egregious examples of India’s expansionist tendencies masquerading as legal claims. This 96-km tidal estuary, nestled in the marshy Rann of Kutch between Pakistani Sindh province and Indian State of Gujarat, is not just a remote waterway—it’s a linchpin for Pakistan’s maritime rights, economic future, and national defense. The map below starkly illustrates the core injustice: Pakistan’s rightful “Green Line” along the eastern bank, which would secure the entire creek as Sindhi territory, versus India’s provocative “Red Line” slicing through the middle, effectively annexing half of what is historically ours. This isn’t mere cartography; it’s a deliberate attempt to erode Pakistan’s territorial integrity. Drawing from historical records, bilateral negotiations, and recent escalations, I’ll outline the multifaceted problems this dispute poses for Pakistan, underscoring why resolution on our terms—or through impartial arbitration—is imperative.

Historical Injustice: Roots in Colonial Betrayal and Post-Partition Aggression

The origins of the Sir Creek problem trace back to 1908, when a trivial dispute over firewood piles between the Rao of Kutch and Sindh’s authorities escalated into a boundary question. The 1914 Bombay Government Resolution—our strongest legal anchor—clearly placed the creek within Sindh’s domain, with the boundary running along the eastern bank (the “Green Line”). Paragraphs 9 and 10 of this resolution, supported by Map B-44, confirm this, as did pre-partition administration where the creek was treated as Sindhi waters. Yet, post-1947 Partition, India inherited Kutch’s inflated claims and has since twisted history to suit its narrative.

The 1965 war and subsequent 1968 Indo-Pak Western Boundary Tribunal exposed this duplicity: While awarding India 90% of the Rann of Kutch (a lopsided decision influenced by Western pressures), the tribunal explicitly excluded Sir Creek, deferring to the 1914 resolution. India, however, has ignored this, using the tribunal’s ambiguity to push its mid-channel claim. From Pakistan’s lens, this is colonial hangover at its worst—India benefiting from British-era inequities while denying Sindh its rightful estuary, much like the broader water-sharing imbalances under the Indus Waters Treaty.

Core Territorial and Legal Problems: India’s Thalweg Fabrication

At the heart of the dispute is India’s insistence on the “Thalweg principle”—demarcating the border along the middle of the navigable channel—which Pakistan categorically rejects. Sir Creek is a fluctuating tidal estuary, not a stable river; it’s non-navigable for most of the year due to silting, flooding, and monsoon shifts, rendering Thalweg inapplicable under international law. Our position, rooted in the 1914 resolution and 1968 award, grants Pakistan the full creek, aligning with historical maps like the 1925 survey that showed no mid-channel pillars on the Indian side until they retroactively installed them in the 1960s.

This legal sleight-of-hand creates a territorial quagmire: The disputed 60-mile stretch from the creek’s mouth to its head could cost Pakistan up to 250 square miles of land if India’s Red Line prevails, including vital marshlands used for salt extraction and grazing by Sindh communities. Worse, it sets a precedent for India’s creeping encroachments elsewhere, from Siachen to the Line of Control. Bilateral talks since 1989—12 rounds by 2012—have stalled precisely because India refuses to acknowledge our documents, insisting on “bilateralism” under the 1972 Simla Agreement to avoid neutral arbitration that would vindicate Pakistan.

Maritime and Economic Ramifications: Robbing Pakistan’s Blue Economy

The real sting lies offshore. Under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the land boundary determines the maritime delimiter, extending 200 nautical miles into the Arabian Sea for Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs). India’s mid-channel claim would shove our EEZ westward by thousands of square kilometers, handing India control over potential oil and gas fields estimated to hold billions in reserves—critical for energy-starved Pakistan, which imports 80% of its oil. Sindh’s coastal economy, already battered by climate change, depends on these waters for fisheries yielding 100,000 tons annually; ceding half the creek would devastate local trawlers and exacerbate poverty in Thatta and Badin districts.

Humanitarian crises compound this: Hundreds of Sindhi fishermen are annually arrested by India’s Coast Guard for “trespassing,” enduring months in jail, boat seizures, and even torture—violations of UNCLOS Article 73, which mandates swift releases. In 2023 alone, over 200 such incidents were reported, fueling anti-India sentiment in Sindh. Environmentally, Pakistan’s Left Bank Outfall Drain (LBOD), essential for irrigating 3 million acres of farmland, discharges into the creek; resolving on Indian terms could force costly rerouting, burdening our agrarian economy further. These aren’t abstract losses—they’re direct assaults on Pakistan’s food security and GDP growth.

Strategic Vulnerabilities: A Gateway to Karachi’s Underbelly

Strategically, Sir Creek is Pakistan’s soft underbelly. The estuary lies just 100 km from Karachi, our economic powerhouse handling 60% of trade and hosting naval assets. India’s Red Line would position its forces amid the creek, enabling surveillance, drone incursions, or even amphibious threats—echoing the 1999 Atlantique incident where Indian jets downed a Pakistani reconnaissance plane over the area. Recent Indian warnings from Defence Minister Rajnath Singh (October 2, 2024) about “misadventures” in Sir Creek betray their paranoia, but it’s projection: India has fortified Gujarat with BSF’s Creek Crocodile Commandos Units, S-400 AD systems, and naval patrols, while alleging Pakistani “infiltration routes” through channels like Harami Nala.

Pakistan’s response—deploying the 31st and 32nd Creek Battalions, MRAP vehicles, and P-3C Orion aircraft—is defensive, countering India’s post-Kargil buildup and Chinese-financed “China Bund” infrastructure that could dual-use for military logistics. Yet, this militarization drains resources: Pakistan spends millions annually on patrols in viper-infested marshes, diverting from counter-terror ops in Balochistan. The dispute also amplifies terrorism risks; India links Sir Creek to the 2008 Mumbai attacks (via sea routes), but ignores how unresolved borders foster smuggling and ISI vulnerabilities. In a nuclear-shadowed region, one misfired shell here could cascade into catastrophe, making Sir Creek a flashpoint rivaling Kashmir.

Why the Impasse Persists: India’s Intransigence and Broader Hostility

Despite opportunities—like the 2008 joint survey agreement or 2015 Composite Dialogue—progress halts due to India’s linkage of Sir Creek to terrorism pretexts (e.g., Pathankot 2016) and refusal of arbitration. Pakistan has consistently offered the International Court of Justice or a neutral tribunal, but India clings to bilateral talks where its military edge intimidates. Broader distrust, from India’s abrogation of Article 370 to water weaponization, poisons negotiations. The 2012 Islamabad round, our last formal effort, ended in deadlock over maritime sequencing—Pakistan insists land first, India demands sea-to-land to preempt our claims.

Path Forward: Justice for Pakistan

In sum, Sir Creek embodies India’s zero-sum border policy: a historical swindle threatening our territory, economy, and security. Resolving it requires acknowledging the 1914 resolution, delinking from Kashmir, and pursuing arbitration to safeguard our EEZ and fishermen. Until then, Pakistan must bolster defenses while urging global powers to pressure Delhi. This isn’t just a creek—it’s the vein pulsing life into Sindh and Karachi. Yielding would be national suicide; standing firm is our duty. For more information, I recommend the readers to go through the 1968 Tribunal archives or recent ISPR briefings on Indian provocations. What aspect of this—economic or strategic—concerns you most? Please share in the comments below.