(By Khalid Masood)

India’s recent threats to restrict the flow of rivers into Pakistan, particularly following the Pahalgam terror attack on April 22, 2025, have escalated tensions in an already volatile region. These threats challenge the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT), a 1960 agreement that has historically governed water sharing between India and Pakistan, surviving wars and diplomatic crises.

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the scenario, addressing historical context, legal implications, Pakistan’s dependence, environmental and geopolitical repercussions, the ethics of water weaponization, the need for diplomacy, and Pakistan’s internal response. The study draws on recent reports, historical data, and international perspectives to evaluate the crisis and propose solutions.

1. Historical Context – The Indus Waters Treaty (1960): A Legacy of Peace and Prudence

In an era of intense rivalry and mistrust, the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT), signed on September 19, 1960, in Karachi by Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Pakistan’s President Ayub Khan, stands as a remarkable triumph of diplomacy. Brokered by the World Bank after nine long and arduous years of negotiations, the treaty emerged from the chaos of the 1947 partition, which had left the lifeblood of the Indus Basin dangerously divided: India held the headworks, Pakistan inherited the canals.

Recognizing the potential for perpetual conflict, the World Bank proposed a bold and pragmatic solution. It offered not just mediation, but substantial funding through the Indus Basin Development Fund, supported by Australia, Canada, West Germany, New Zealand, the UK, and the US. This initiative fortified Pakistan’s water infrastructure and ensured a dependable supply of water for a growing nation.

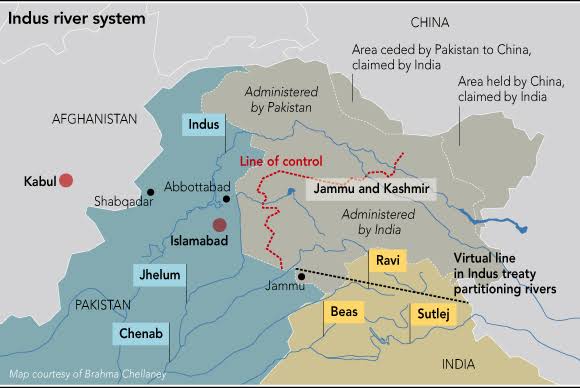

The treaty’s framework was clear and just:

- The Western Rivers (Indus, Jhelum, Chenab), constituting 80% of the basin’s flow (~99 billion cubic meters annually), were allocated to Pakistan. India retained limited rights for non-consumptive use like hydropower under strict monitoring.

- The Eastern Rivers (Ravi, Sutlej, Beas), with lesser flow (~41 billion cubic meters), were assigned to India.

More than a document, the IWT became an enduring instrument of peace, weathering wars (1948, 1965, 1971), skirmishes (Kargil 1999), and countless diplomatic standoffs. It remains a global model of technical, depoliticized water-sharing, overseen by the Permanent Indus Commission (PIC), neutral experts, and international arbitration.

2. India’s Threat – A Breach of International Law

Violation of the Treaty

India’s announcement on April 23, 2025, to hold the IWT in abeyance, citing Pakistan’s alleged support for the Pahalgam attack, marks the first explicit suspension of the treaty. This followed escalatory measures, including closing the Wagah-Attari border and expelling diplomats. Indian officials, including Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri and Union Water Minister CR Paatil, vowed to block water flows, with reports of India releasing 28,000 cusecs from the Chenab River after a 24-hour blockade, triggering flood alerts in Pakistan. Such actions violate Article II(1) of the IWT, which guarantees Pakistan’s “unrestricted use” of the western rivers, and Article IV(3), which prohibits India from materially affecting their flow. The expansion of the Ranbir Canal to 150 cumecs (over 5,200 cusecs) exceeds the treaty’s irrigation limits (1,000 cusecs in summer, 350 cusecs in winter), constituting a clear breach.

Legal Implications

Unilateral suspension of the IWT violates international law, as the treaty lacks provisions for unilateral termination or suspension. The 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT), though not ratified by Pakistan and not acceded to by India, codifies customary international law under Article 62, requiring a “fundamental change in circumstances” for treaty termination. The International Court of Justice (ICJ) has set a high threshold for this, as seen in the 1997 Gabcíkovo-Nagymaros case, where political and economic changes were deemed insufficient. India’s cited reasons—population dynamics, clean energy needs, and Pakistan’s alleged terrorism—do not meet this threshold, as they are not directly linked to the treaty’s core objective of water sharing. Pakistan has labeled the suspension an “act of war” and is preparing legal challenges at the ICJ, Permanent Court of Arbitration, and World Bank, supported by the 2023 arbitration ruling affirming the treaty’s validity.

UN and World Bank’s Role

The World Bank, as a treaty signatory and mediator, is responsible for facilitating dispute resolution through neutral experts or arbitration, as seen in the 2022 appointments of a neutral expert (Michel Lino) and a Court of Arbitration. However, India’s refusal to engage in PIC meetings since 2024 and its suspension letter citing “no third-party intervention” undermine the World Bank’s role. The UN, while not directly involved, has a stake in enforcing customary international law on transboundary rivers, as upper riparians (India) cannot legally deny water to lower riparians (Pakistan). The lack of a robust response from these institutions, despite Pakistan’s appeals, raises questions about their ability to enforce compliance amid geopolitical pressures, particularly given India’s growing global influence.

3. Pakistan’s Dependence on Indus Water

Agricultural Reliance

Pakistan’s economy is heavily agrarian, with agriculture contributing 24% to GDP and employing 37.4% of the workforce, per Pakistan’s 2024 economic survey. Over 80% of its irrigated agriculture, covering 18 million hectares, depends on the Indus Basin, particularly the western rivers. The Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab supply water for key crops like wheat, rice, sugarcane, and cotton, which are critical to Pakistan’s food and textile industries. The canal system, rooted in colonial-era infrastructure, relies on consistent river flows, making Pakistan vulnerable to upstream disruptions.

Food Security Risk

A water stoppage would devastate Pakistan’s food production, as the western rivers feed 80% of its irrigated agriculture. Ghasharib Shaokat of Pakistan Agriculture Research warned that erratic water flows could reduce yields of wheat, rice, and sugarcane, increasing costs and threatening food security for a population of 247.5 million. In 2023, floods from India’s Sutlej River release destroyed crops worth tens of thousands of pounds, illustrating the sector’s fragility. A sustained blockade could lead to widespread crop failures, price spikes, and import dependency, exacerbating economic instability.

Humanitarian Crisis

Blocking water flows would trigger a humanitarian crisis, with millions facing water scarcity for drinking, irrigation, and hydropower (33% of Pakistan’s hydropower comes from the Indus Basin). Farmers like Ali Haider Dogar, already reeling from 2023 floods, fear starvation and displacement. Naseer Memon, a Pakistani water expert, warned of “disastrous” consequences, including mass migration, hunger, and social unrest, particularly in Punjab and Sindh, where 80% of the population depends directly or indirectly on agriculture. The suspension of hydrological data sharing, critical for flood forecasting, heightens risks during the monsoon season (June–September).

4. Environmental and Geopolitical Repercussions

Ecological Disaster

Abrupt water stoppage could lead to desertification, drying of rivers, and loss of biodiversity in Pakistan. The Indus Basin supports wetlands, fisheries, and ecosystems critical to millions. Over 70% of the Upper Indus’s flow comes from glacial (26%) and seasonal snow (44%) melt, making it vulnerable to Himalayan deglaciation. Reduced flows could exacerbate water scarcity, degrade soil fertility, and collapse aquatic ecosystems. Sudden silt flushing from Indian dams, as warned by experts, could damage downstream infrastructure and agriculture in Pakistan, amplifying environmental harm.

Regional Instability

The IWT’s collapse risks armed conflict in a nuclearized region. Pakistan’s military doctrine permits a kinetic response to water scarcity, viewing the Indus as a lifeline. Pakistan’s April 24, 2025, threat to suspend all bilateral agreements, including the 1972 Simla Accord, signals escalation potential. The May 7–11 clashes, involving airstrikes and drone attacks, underscore the fragility of peace. A water war could destabilize South Asia, home to 1.9 billion people, disrupting trade, energy, and security.

Global Ramifications

South Asia’s instability would have global consequences, given its population density and nuclear capabilities. The region’s role in global food and textile markets means disruptions could spike commodity prices. India’s actions could embolden other upper riparians (e.g., China on the Brahmaputra) to weaponize water, undermining transboundary agreements worldwide. The international community, including the US, UK, and China, has urged restraint, with trade sanctions and mediation proposed to prevent escalation.

5. India’s Weaponization of Water – A Dangerous Precedent

Water as a Weapon

India’s threats, exemplified by CR Paatil’s vow to block “not a drop of water” and the Chenab’s temporary blockade, mark a shift toward hydro-aggression. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s 2016 statement, “blood and water cannot flow together,” foreshadowed this strategy. Using water to coerce Pakistan, especially after the Pahalgam attack, politicizes a shared resource, setting a precedent for other nations to exploit transboundary rivers during conflicts.

Moral Argument

Weaponizing water, a basic human need, raises profound ethical concerns. Denying Pakistan’s 247.5 million people access to water for agriculture and drinking violates principles of humanity and equity. The IWT was designed to depoliticize water, ensuring cooperation despite hostility. India’s actions undermine this legacy, prioritizing geopolitical leverage over shared survival in a climate-stressed region.

Human Rights Violation

Denying water access violates international human rights norms, including the UN’s recognition of water as a human right (Resolution 64/292, 2010). The potential for mass starvation, displacement, and ecological collapse in Pakistan constitutes a humanitarian crisis that contravenes customary international law on transboundary rivers, which obligates upper riparians to avoid causing significant harm to lower riparians. India’s suspension risks international condemnation and legal repercussions.

6. Need for Diplomacy, Dialogue, and Water Cooperation

Call for Peace

Diplomacy is the only path to de-escalate this crisis. India and Pakistan must resume PIC meetings and engage in technical dialogue to address disputes, as the IWT’s mechanisms have historically resolved conflicts (e.g., Baglihar Dam arbitration). Joint management of the Indus Basin, factoring in climate change, could rebuild trust and prevent escalation.

Role of International Community

The UN, World Bank, and major powers (US, UK, China) must mediate to enforce the IWT and prevent a humanitarian crisis. The UK’s David Lammy urged treaty compliance, while Donald Trump’s trade-based diplomacy secured a ceasefire on May 10, 2025. The World Bank should expedite arbitration, and the UN could invoke environmental and human rights frameworks to pressure India. Neutral facilitators like Saudi Arabia and the UAE, successful in 2019, could bridge the trust gap.

Water as a Bridge, Not a Weapon

The Indus River should be a source of cooperation, not conflict. Initiatives like the UNEP-backed “Living Indus” program promote ecosystem restoration and data-sharing, offering a model for joint climate-resilient management. India and Pakistan could explore cooperative hydropower projects or water-efficient irrigation to address shared challenges, fostering peace and prosperity.

7. Public Awareness and Unity in Pakistan

National Preparedness

Pakistan must urgently enhance water security by building reservoirs (e.g., Diamer-Bhasha, Mohmand dams), modernizing irrigation (30% of canal water is lost to seepage), and adopting water-efficient agriculture (60% wastage in outdated systems). The Cholistan Canal project could bolster resilience. Investments in hydropower and storage on the Chenab, Jhelum, and Indus would assert riparian rights and mitigate floods and droughts.

Public Vigilance

Citizens must understand the crisis’s gravity, as water scarcity threatens livelihoods and survival. Media campaigns, educational programs, and community forums can raise awareness about conservation and the IWT’s importance. Social media platforms, like X, where posts by @zarrar_11PK and @nabilajamal_ highlighted India’s actions, can amplify public discourse.

National Unity

Water security is a unifying national cause. Political parties, civil society, and farmers’ associations, like Khalid Khokhar’s Farmers’ Association, must rally around reforms and legal action. Public protests, as seen at Karachi University, and crowdfunding efforts like the Mohmand Dams Fund demonstrate Pakistan’s resolve. Unity will strengthen Pakistan’s diplomatic and legal stance internationally.

Conclusion: Water Must Not Be a Weapon

India’s threats to block Pakistan’s water aren’t just hostile—they’re inhumane, illegal, and catastrophic. The Indus Waters Treaty has long served as a buffer against war and famine. Its collapse would push 247 million Pakistanis toward an abyss.

This is not merely a legal or political dispute; it is a battle for survival, for dignity, and for the right to exist. The world must not remain a silent spectator.

Let water be a source of life, not death. Let it be a bridge, not a bomb.

Pakistan stands united, prepared, and determined to protect its waters—its soul.

“May the rivers of the subcontinent flow with justice, not vengeance; with peace, not poison.”

Excellent initiative.