(By Khalid Masood)

Trump’s Golden Dome represents one of the most ambitious and contentious defence initiatives of the second Trump administration. Announced via Executive Order 14186 in January 2025 as the “Iron Dome for America” before being rebranded in May, the project seeks to establish a comprehensive, layered missile defence shield for the United States homeland. It aims to counter a broad spectrum of aerial threats—including ballistic missiles, hypersonic glide vehicles, cruise missiles, and drone swarms—from adversaries ranging from rogue states such as North Korea to peer competitors like Russia and China.

Drawing rhetorical inspiration from Israel’s Iron Dome, which intercepts short-range rockets with high effectiveness, Golden Dome is vastly more expansive. It envisions a “system of systems” integrating ground-, sea-, air-, and especially space-based components to achieve near-impenetrable protection. President Trump has described it as completing the vision begun by Ronald Reagan’s Strategic Defence Initiative in the 1980s, but leveraging modern advances in low-cost space launches, miniaturisation, and commercial technology.

As of January 2026, the programme has secured significant initial funding and generated intense debate. Supporters view it as essential “peace through strength” in an era of escalating missile threats, while critics question its technical realism, astronomical costs, and potential to destabilise global strategic balance.

Origins and Political Evolution

The project’s roots lie in Trump’s 2024 campaign pledges to bolster homeland defence against emerging hypersonic threats. Upon returning to office, he issued Executive Order 14186 on 27 January 2025, directing the Department of Defence (DoD) to develop a next-generation missile shield. By May 2025, during an Oval Office briefing, the initiative was formally named Golden Dome for America, with U.S. Space Force General Michael Guetlein appointed as direct-reporting programme manager.

Congress has played a pivotal role. The FY2025 reconciliation bill (the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act”) provided an initial $23–25 billion “down payment”. Bipartisan Golden Dome caucuses formed in both chambers, and legislation such as the IRONDOME Act and GOLDEN DOME Act has advanced related priorities. The FY2026 defence appropriations bill, finalised in January 2026, allocates approximately $13.4 billion for integrated support (including $9.6 billion for Missile Defence Agency programmes and $3.8 billion for Space Force efforts), while expressing frustration over the Pentagon’s lack of transparency on spending details, master schedules, performance metrics, and system architecture.

Key figures include Secretary of Defence Pete Hegseth, who has emphasised phased deployment prioritising high-threat areas, and industry partners such as Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, Anduril, and others awarded early prototype contracts.

What Is the Golden Dome? Technical Breakdown

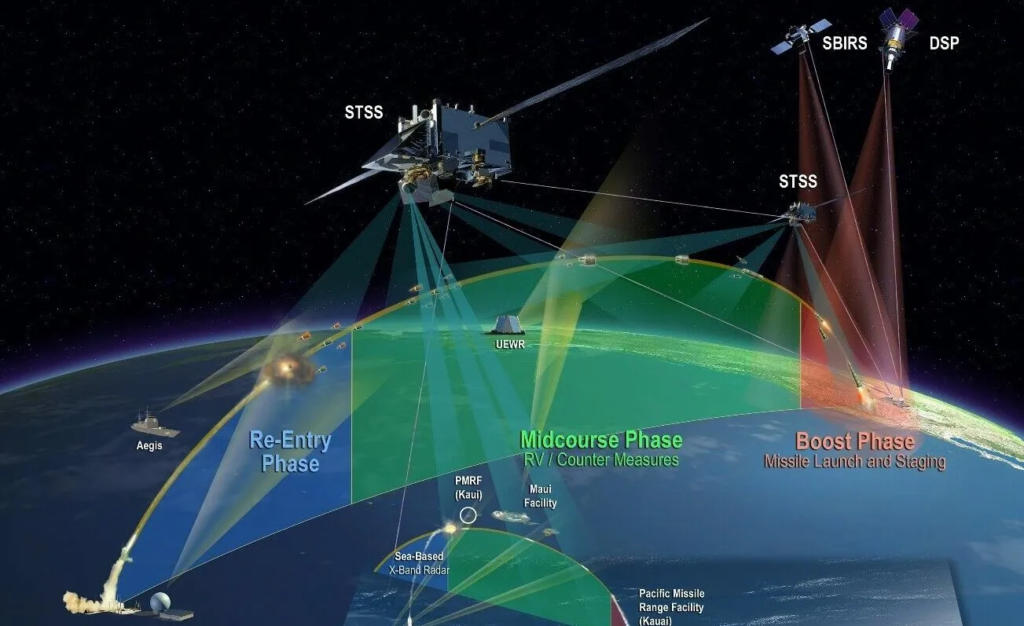

Golden Dome is conceived as a multi-layered architecture rather than a single system. Core elements include:

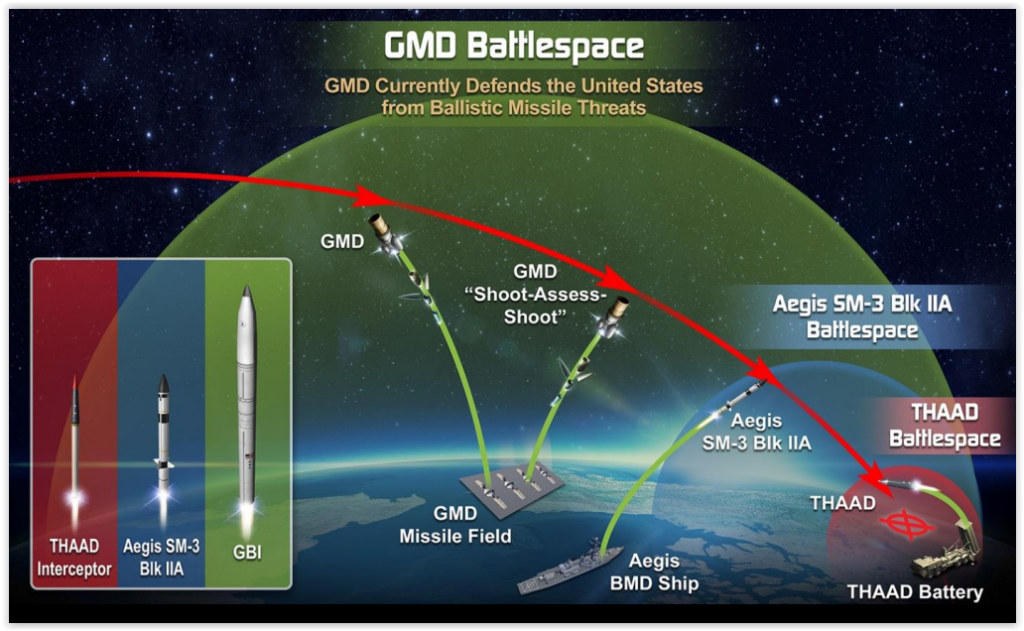

- Ground- and sea-based layers: Expansion of existing capabilities such as Ground-based Midcourse Defence (GMD), Aegis Ashore/Ship systems, Terminal High Altitude Area Defence (THAAD), and Patriot batteries for terminal-phase intercepts.

- Air-based components: Potential integration of airborne platforms for boost-phase or mid-course engagement.

- Space-based dominance: The project’s most innovative—and controversial—aspect. This encompasses the Hypersonic and Ballistic Tracking Space Sensor (HBTSS) constellation for persistent detection, proliferated low-Earth-orbit interceptors for boost- and mid-course kills, and possibly directed-energy weapons (e.g., lasers). The emphasis on space aims to enable global coverage and counter fast, manoeuvrable hypersonics.

The approach is phased: near-term enhancements to sensor networks and tracking, followed by demonstrations and incremental deployment. It builds on programmes like the Tactical Surveillance, Reconnaissance, and Tracking (TacSRT) initiative and seeks commercial partnerships for cost efficiency.

Timeline and Progress in 2026

President Trump has maintained an aggressive schedule: initial capabilities “very early” with the reconciliation funding, and full operational status by the end of his term in 2029 (roughly three to four years from announcement). A major test was reportedly scheduled for late 2028 to demonstrate progress.

As of January 2026, progress remains in early stages. The Space Force has awarded small prototype contracts, industry briefings continue, and some sensor enhancements draw from existing programmes. However, no finalised architecture or public master plan exists. Independent assessments from think tanks such as CSIS and the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) suggest demonstrations under ideal conditions might occur by the late 2020s, but meaningful nationwide capability would likely extend into the 2030s. Pentagon officials have indicated phased rollouts, but congressional appropriators have criticised delays in providing detailed plans.

Costs: From $175 Billion Promise to Trillions in Estimates

The White House estimates total costs at around $175 billion, with the initial $23–25 billion as a deposit. The FY2026 budget incorporates further allocations, pushing cumulative commitments higher.

Independent projections diverge sharply. The CBO has estimated $161–$542 billion for limited space-based interceptor elements alone over 20 years. Studies from the American Enterprise Institute and others range from $252 billion (for tactical defence against drones/cruise missiles) to $3.6 trillion (for comprehensive peer-threat coverage, including sustainment and replenishment of orbital assets). These variances stem from constellation size, orbital decay requiring frequent replacements, and integration challenges. Historical missile defence programmes have routinely exceeded initial estimates, raising concerns about opportunity costs and fiscal sustainability.

Feasibility: Technical, Strategic, and Political Challenges

Proponents highlight technological maturity—cheaper launches, commercial innovation, and existing building blocks—as enabling partial successes against rogue-state threats. Enhanced tracking could improve deterrence and integrate with allied systems.

However, feasibility faces steep hurdles. Space-based interceptors contend with orbital mechanics (e.g., “absenteeism” where satellites are out of position), vulnerability to anti-satellite weapons, and the need for thousands of units to ensure coverage. Countermeasures such as decoys, saturation salvos, and cheaper offensive missiles could overwhelm defences. Experts from CSIS, the Arms Control Association, and others describe full “impenetrable dome” protection against peer adversaries as illusory, likening it to past overpromises like Reagan’s SDI.

Strategically, the programme risks provoking arms races, as Russia and China have warned of undermined mutual deterrence and space militarisation. Politically, congressional oversight remains strained by perceived secrecy, with recent appropriations demanding detailed reporting.

Geopolitical Dimensions and Controversies

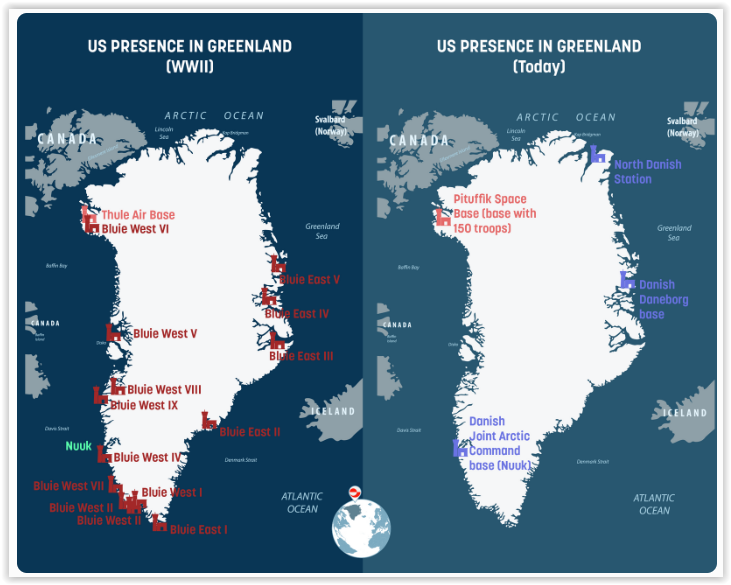

Golden Dome intersects with broader Arctic strategy, particularly Trump’s push for U.S. influence over Greenland. In January 2026, he linked the island’s strategic position to basing sensors and interceptors for northern coverage against Russian/Chinese threats. After tariff threats against Denmark and European allies, Trump announced a “framework” deal involving mineral rights access and potential Golden Dome collaboration, averting escalation but straining NATO ties. Denmark has expressed openness to talks on Arctic security, while critics warn of sovereignty risks and alliance damage.

Internationally, the project could strain relations with Russia and China, who view it as offensive posturing, while offering cooperation opportunities with allies like Canada (invited to participate).

Potential Outcomes and Looking Ahead

Optimistic scenarios foresee phased improvements in detection and limited defence, bolstering deterrence. Pessimistic views predict delays, cost overruns, and scaled-back ambitions amid fiscal and technical realities. Alternatives include fortifying existing systems, pursuing diplomacy to manage threats, or balancing offence and defence.

Conclusion

Golden Dome embodies a bold vision of homeland invulnerability through technological superiority and resolute leadership. With substantial funding committed and early momentum, it signals America’s determination to counter evolving missile dangers. Yet the initiative confronts profound technical barriers, escalating costs, strategic risks, and geopolitical tensions—particularly evident in the Greenland saga and congressional oversight demands.

In an age of great-power competition, the true measure of success will be whether Golden Dome delivers tangible protection without igniting new instabilities or fiscal burdens. As debates intensify in 2026 and beyond, the project tests not only engineering prowess but also the wisdom of pursuing near-perfect defence in an imperfect world.