Introduction: A Community Caught in the Crossfire of History

A young girl writes a poem where she asks a simple question — one which no one can answer. She asks, “Who am I?” Her forefathers were born in India, they immigrated to Pakistan, and she was born in Bangladesh. India has given up on them a long time back, Bangladesh will not accept them as the children of the land and Pakistan will not take them back. She says that she has many names ‘Bihari’, ‘Maura’, ‘Muhajir’, ‘Non-Bangalee’, ‘Marwari’, ‘Urdu-speaker’, ‘Refugee’, and ‘Stranded Pakistani’. But she only wants one identity: Human.

This is the state of the 1.6 lakh camp-based Urdu-speaking community in Bangladesh. At the Geneva camp now there are about 50 thousand Urdu speaking Indian & Pakistani peoples are living.

After the partition of India in 1947, faced with large-scale communal riots on both sides of the border, a few hundred thousand Muslims from Bihar, Kolkata, Uttar Pradesh, Maddhya Pradesh and as far away as Hyderabad came to the then East Pakistan. Biharis shared Islam with the Bengali majority but remained culturally and linguistically distinct. Perceived as loyal to unified Pakistan and often benefiting from West Pakistani administration, they became targets of ethnic resentment. The 1971 war unleashed cycles of violence on all sides, leaving the Biharis marginalized, stateless for decades, and struggling for full integration even today.

Historical Background: Migration and Rising Tensions

Following the 1947 Partition, hundreds of thousands of Urdu-speaking Muslims from Bihar and neighboring Indian states migrated to East Pakistan, seeking refuge from communal violence. By the 1951 census, around 671,000 such refugees had settled there, rising to over 850,000 by 1961. They concentrated in urban areas like Dhaka, Chittagong, and Khulna, often in railway colonies or industrial zones.

Despite shared religion, linguistic and cultural differences fueled tensions. Biharis were seen as supporters of West Pakistani dominance, especially during the Bengali Language Movement of the 1950s and 1960s. Economic disparities—many Biharis held better jobs in jute mills or administration—bred resentment. The postponement of the 1970 National Assembly session after the Awami League’s landslide victory escalated frustrations, leading to early 1971 unrest where non-Bengalis, particularly Biharis, faced targeted attacks.

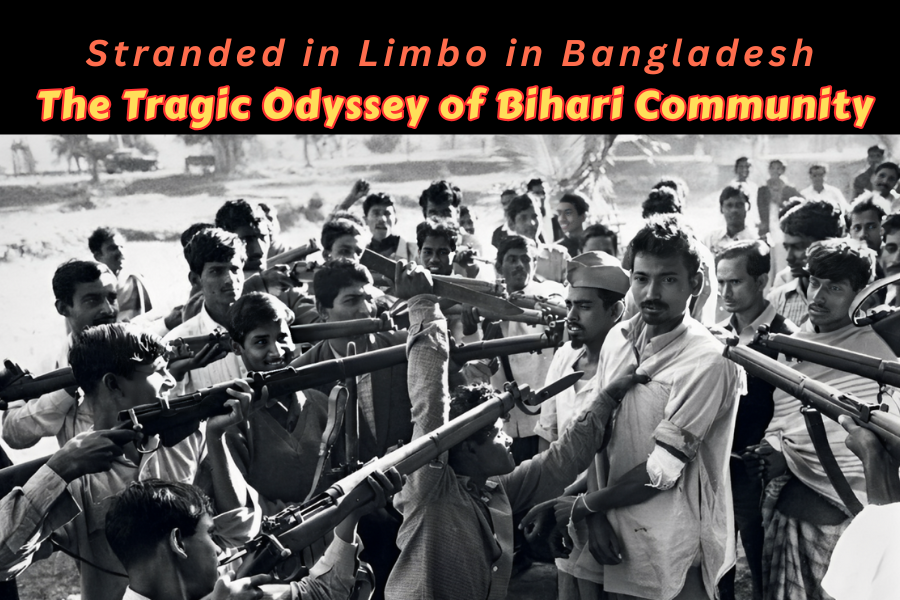

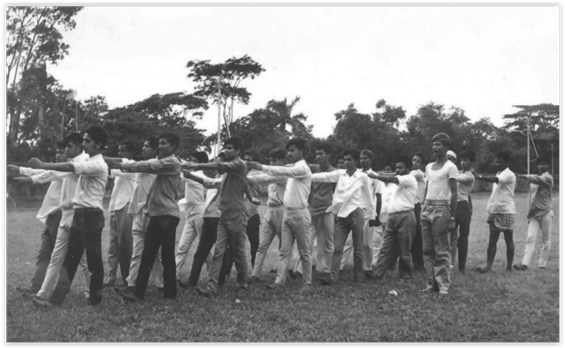

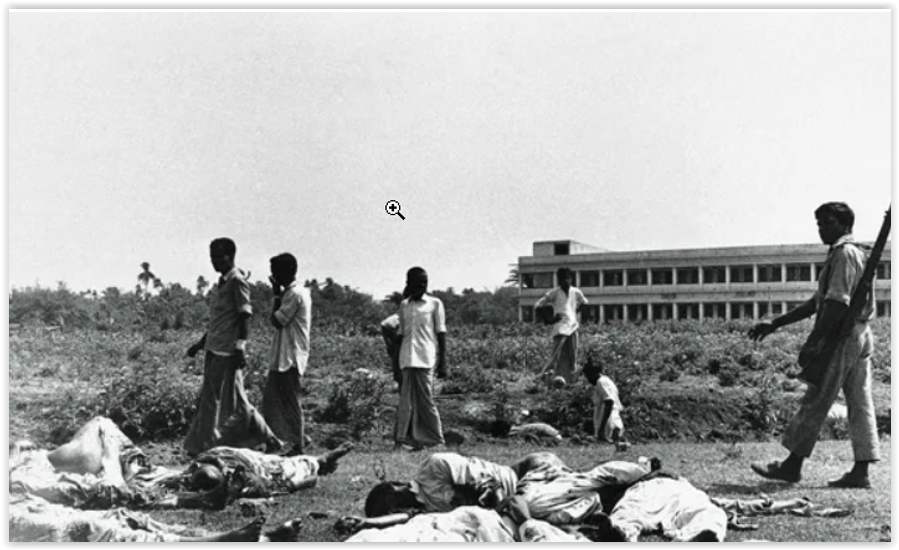

The Atrocities of 1971: Ethnic Violence Against Biharis

As Bengali nationalism surged in March 1971, widespread violence erupted against Biharis, viewed as symbols of Pakistani unity. Mobs attacked neighborhoods, killing, looting, and burning homes. These assaults preceded the Pakistani military’s Operation Searchlight on March 25, 1971, which the army justified partly as protection for non-Bengalis.

Key incidents include:

- Chittagong: In early March, hundreds of Biharis were killed in areas like Firingi Bazar.

- Khulna: On March 28, militants besieged jute mill settlements, slaughtering hundreds to thousands in brutal attacks.

- Santahar: Thousands reportedly perished over days in late March, with eyewitnesses describing systematic killings.

- Other sites like Jessore and Panchabibi saw similar massacres of Biharis.

Death estimates vary sharply: Bihari leaders claimed up to 500,000; Pakistani sources around 250,000; scholars like R.J. Rummel estimated 150,000; while conservative figures (e.g., Minorities at Risk) suggest 25,000–50,000. Historian Sarmila Bose documented xenophobic reprisals, including against women and children, arguing these were often overlooked in dominant narratives. Violence was mutual—Biharis later faced reprisals for alleged collaboration—but early anti-Bihari pogroms marked a dark ethnic cleansing phase.

International attention focused on Pakistani military atrocities against Bengalis, amplified by Indian diplomacy, sidelining Bihari suffering amid Cold War complexities.

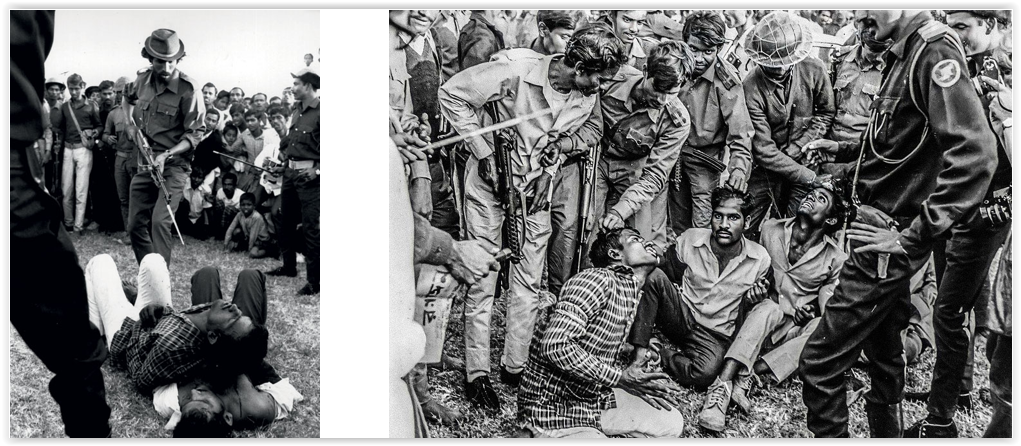

Alignment with Pakistan and Post-War Reprisals

Facing mortal danger, many Biharis aligned with the Pakistani Army for protection, joining militias like Razakars, Al-Badr, and Al-Shams. Motivated by survival and loyalty, these groups countered Mukti Bahini guerrillas but were implicated in crimes against Bengali civilians, intensifying post-independence vengeance.

After Bangladesh’s victory in December 1971, Biharis labeled “collaborators” endured internment, property confiscation, and killings. Survivors were herded into Red Cross camps, becoming “stranded Pakistanis.”

The Unfulfilled Desire for Repatriation to Pakistan

Due to their staunch pro-Pakistan stance during the 1971 war and subsequent persecution, the vast majority of Biharis expressed a strong desire to migrate to Pakistan, viewing it as their ideological homeland rooted in loyalty to the Two-Nation Theory. Many saw themselves as full Pakistani citizens whose status remained unchanged post-separation. Under the 1974 Tripartite Agreement between Pakistan, Bangladesh, and India, Pakistan agreed to accept around 170,000 Biharis, prioritizing civil servants, military personnel, divided families, and hardship cases. Approximately 170,000–178,000 were eventually repatriated over the years, with most settling in urban Sindh, particularly Karachi, where they integrated into the Muhajir community.

However, repatriation efforts faced significant hurdles. Pakistani leaders, including under Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and later governments, showed initial commitment but slowed the process due to resource constraints and domestic politics. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, attempts to bring larger groups—such as a planned flight in 1989 and a small batch of 323 families in 1993 settled in Punjab—were canceled or stalled amid fierce opposition. Sindhi nationalists, including groups like the Sindhi National Alliance and factions of the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), vehemently protested, fearing that an influx of Urdu-speaking Biharis would further alter Sindh’s demographic balance, exacerbate ethnic tensions, and strengthen Muhajir political dominance in cities like Karachi. These fears contributed to riots and strained coalitions, halting further large-scale repatriation by 1993. While some efforts focused on Punjab settlements to avoid Sindh’s sensitivities, overall political reluctance left hundreds of thousands stranded, underscoring a tragic irony: a community that sacrificed for Pakistan’s unity was largely abandoned by it.

Post-Independence Marginalization and the Path to Citizenship

Partial repatriation left most behind. Denied citizenship initially, they lived in limbo in over 100 camps with poor conditions.

Landmark rulings changed this: A 2003 High Court decision granted citizenship to some; the pivotal 2008 judgment affirmed it for those minors in 1971 or born later—covering most of the estimated 300,000 Biharis. By 2025, the majority hold legal Bangladeshi citizenship, enabling voting and IDs.

Current Challenges: From Legal Citizenship to Full Integration

Despite formal recognition, many Biharis remain in squalid camps, facing discrimination, poverty, limited education, and employment barriers. Overcrowding, lack of amenities, and social stigma persist. Younger generations often embrace Bangladeshi identity, but full societal acceptance lags.

Conclusion: Toward Reconciliation and Dignity

The Bihari saga highlights the enduring human costs of partition and ethnic conflict: cycles of violence, statelessness, and incomplete healing. While Bangladesh has progressed toward legal inclusion, true integration demands addressing discrimination and historical grievances. Acknowledging atrocities on all sides—against Bengalis and Biharis alike—could pave the way for reconciliation, ensuring this community’s dignity in the nation they now call home.