(By Khalid Masood)

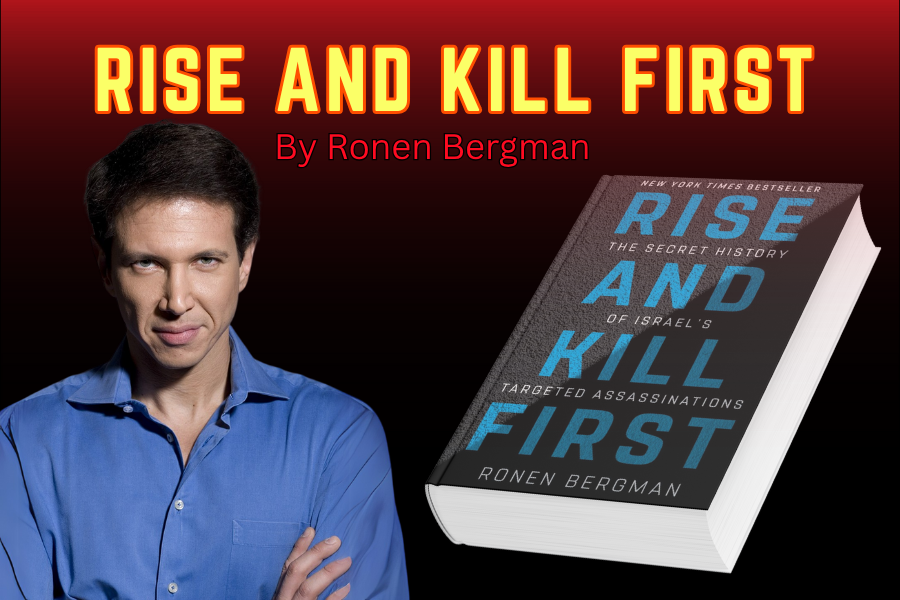

In Rise and Kill First: The Secret History of Israel’s Targeted Assassinations (2018), Israeli investigative journalist Ronen Bergman pulls back the curtain on one of the most secretive facets of Israel’s national security apparatus: its use of targeted killings to neutralize perceived threats. Hailed as a New York Times bestseller and winner of the National Jewish Book Award in History, the book draws on nearly eight years of research, including over 1,000 interviews with Israeli prime ministers, intelligence operatives, and assassins, as well as thousands of classified documents. Bergman’s work reveals that since World War II, Israel has assassinated more individuals—over 2,700 operations—than any other Western nation, employing tactics from poisoned toothpaste to exploding mobile phones. Through meticulous storytelling and ethical reflection, Rise and Kill First not only chronicles Israel’s covert operations but also probes their moral, political, and strategic costs. This article explores the book’s significance, delves into three pivotal case studies—Operation Wrath of God, the assassination of Mahmoud al-Mabhouh, and the targeting of Iranian nuclear scientists—and assesses its impact on our understanding of state-sponsored assassination.

The Genesis of Israel’s Assassination Doctrine

The book’s title, derived from the Talmudic precept “If someone comes to kill you, rise up and kill him first,” encapsulates Israel’s preemptive approach to survival, rooted in its precarious geopolitical reality. Bergman traces this doctrine to the pre-state Zionist militias like Bar Giora (1907) and Haganah, which evolved into the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), Mossad, Shin Bet, and the elite Caesarea unit. The Holocaust, Bergman argues, cemented Israel’s belief in existential vulnerability, justifying extreme measures to thwart annihilation. From the 1940s, targeting British colonial officials and Nazi collaborators, to the post-1948 era, eliminating Palestinian, Hezbollah, and Iranian figures, Israel’s intelligence services honed assassination as a substitute for conventional war. Bergman’s access to figures like Shimon Peres, Ehud Barak, and Benjamin Netanyahu reveals a state apparatus where young operatives routinely pitched kill orders to prime ministers, blending tactical precision with moral ambiguity.

Bergman’s narrative spans decades, detailing operations in Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Iran, and beyond. He describes innovative methods—drones, remote-controlled bombs, and cyber sabotage—pioneered by Israel’s “start-up nation” ingenuity. Yet, he underscores the unintended consequences: assassinations often fueled vengeance cycles, radicalized adversaries, and strained diplomatic ties. The book’s strength lies in its balance, neither glorifying nor condemning Israel’s actions but exposing their complexity. Critics like Kenneth Pollack praise its “smart, thoughtful” approach, while John le Carré calls it a “compelling read” for its unflinching detail. However, some, like Philip Weiss, question Bergman’s motives, citing his ties to pro-Israel groups like AIPAC, suggesting a bias despite his left-leaning reputation in Israel.

Case Study 1: Operation Wrath of God (1972-1988)

One of the book’s most gripping accounts is Operation Wrath of God, launched after the 1972 Munich Olympics massacre, where Black September, a Palestinian militant group, killed 11 Israeli athletes. Authorized by Prime Minister Golda Meir, Mossad was tasked with eliminating the perpetrators, marking a shift to systematic global assassinations. Bergman details operations across Europe and the Middle East, including the 1973 killing of Ali Hassan Salameh’s deputy in Paris and the 1979 assassination of Salameh himself in Beirut via a car bomb, which killed eight bystanders. The operation showcased Mossad’s audacity but also its blunders, like the 1973 Lillehammer affair, where agents mistakenly killed an innocent Moroccan waiter, Ahmed Bouchikhi, sparking international outrage and exposing Mossad’s methods. Bergman notes the operation’s mixed legacy: while it disrupted Black September, it radicalized Palestinian factions and cost Israel diplomatically.

Case Study 2: The Assassination of Mahmoud al-Mabhouh (2010)

Bergman’s account of the 2010 assassination of Mahmoud al-Mabhouh, a Hamas arms supplier, in Dubai illustrates Mossad’s modern sophistication and vulnerabilities. On January 19, 2010, a 27-member Mossad team, posing as tourists and tennis players, converged on Dubai’s Al Bustan Rotana hotel. Using false passports and routed communications via Austria, they injected Mabhouh with a paralyzing drug, staging his death as natural. However, CCTV footage captured the team’s movements, exposing Mossad to global scrutiny. Bergman highlights the operation’s tactical success—Mabhouh, a key Iran-Hamas link, was eliminated—but its diplomatic fallout: Dubai’s police chief publicized the footage, straining Israel’s ties with allies like Australia, whose passports were forged. The incident, Bergman argues, enhanced Mossad’s “merciless reputation” but underscored the risks of high-profile operations in a surveillance age.

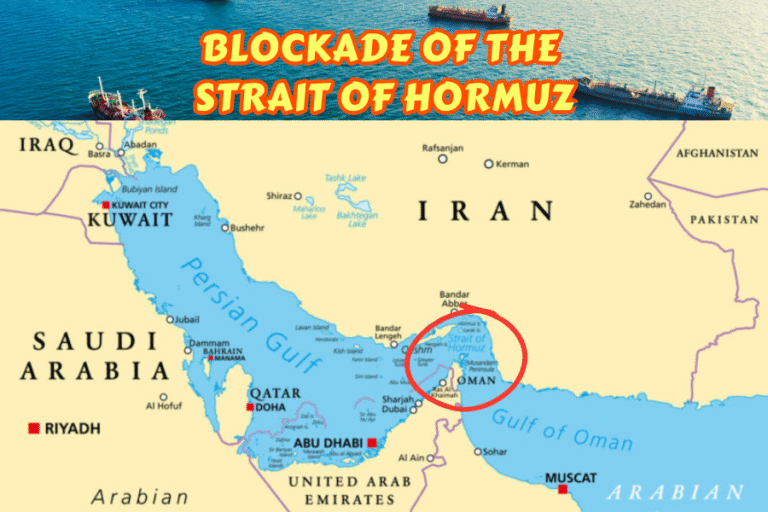

Case Study 3: Targeting Iranian Nuclear Scientists (2007-2012)

Bergman details Israel’s campaign to sabotage Iran’s nuclear program through assassinations, a strategy to avoid full-scale war. Between 2007 and 2012, Mossad and Shin Bet allegedly killed six Iranian scientists, including Masoud Ali Mohammadi and Majid Shahriari, using methods like magnetic bombs attached to cars by motorbike assassins. These operations, often attributed to Israel, delayed Iran’s nuclear ambitions, with Bergman citing estimates of a two-year setback. However, they provoked Iran’s retaliation, including attacks on Israeli diplomats in India and Thailand. Bergman quotes Meir Dagan, Mossad chief from 2002-2011, who saw assassinations as tactical but not strategic, warning they fueled Iran’s resolve. The campaign, lauded for its precision, raised ethical questions about targeting civilians and its long-term efficacy, as Iran’s program persisted.

Ethical and Strategic Reflections

Rise and Kill First confronts the moral quagmire of targeted killings. Bergman quotes Ami Ayalon, former Shin Bet chief, who likened the practice to the “banality of evil,” reflecting operatives’ desensitization to killing. The book reveals internal Israeli debates, with figures like Dagan advocating a two-state solution over endless assassinations. Yet, Bergman notes the Israeli public’s support, driven by Palestinian attacks and perceived intransigence, like Mahmoud Abbas’ Holocaust denial. Critics argue the book lacks a Palestinian perspective, with Iqbal Jassat suggesting it indicts Israel’s “ideologues of death” but falls short of neutrality. Bergman himself faced Mossad’s attempts to disrupt his research, including a 2010 meeting to deter interviewees, underscoring the topic’s sensitivity.

Strategically, Bergman concludes that assassinations are a “tactic, not a strategy.” While they neutralized threats like Hamas’ Yahya Ayyash, killed by an exploding phone in 1996, they often backfired, as with the 1988 assassination of PLO’s Abu Jihad, which derailed peace talks. The book’s final chapters liken targeted killings to an “addictive drug,” per Pollack, curing symptoms but not the underlying conflict. Bergman’s data—2,700 operations since 1948—underscores their scale, yet he warns of diminishing returns, as seen in Gaza’s ongoing violence. The U.S., Bergman notes, adopted Israeli methods post-9/11, with Presidents Bush and Obama escalating drone strikes, raising parallel ethical dilemmas.

Critical Reception and Legacy

Rise and Kill First has been lauded for its depth and daring. The New York Times’ Jennifer Szalai calls it a “humane book about an incendiary subject,” while The Guardian praises Bergman’s “remarkable access” to operatives. Its 753 pages, blending history and thriller-like pacing, earned it accolades from The Economist and BBC History Magazine. However, some readers on Goodreads critique its length and repetition, and its Israeli-centric lens, with only 57 of 66 Amazon reviews praising its historical balance. Bergman’s left-leaning stance, noted by reviewers, contrasts with his AIPAC praise, complicating his perceived objectivity.

The book’s legacy lies in its unprecedented transparency. By exposing operations like the botched 1997 attempt on Hamas’ Khaled Meshal, which cost Israel Jordan’s favor, Bergman challenges Israel’s secrecy culture. His Supreme Court battle for archival access underscores his journalistic rigor, though critics like Weiss argue he serves Israel’s narrative. For scholars and policymakers, Rise and Kill First offers a cautionary tale about assassination’s limits, relevant as drone warfare proliferates globally. Its case studies remain a benchmark for studying covert operations, balancing tactical genius with human cost.

Conclusion: A Mirror to Power

Ronen Bergman’s Rise and Kill First is a tour de force, illuminating Israel’s assassination machine with unmatched detail and nuance. Through case studies like Operation Wrath of God, Mahmoud al-Mabhouh’s killing, and Iran’s nuclear scientists’ targeting, it reveals a nation driven by survival yet haunted by its choices. The book’s ethical probing—echoed by operatives’ regrets and public ambivalence—invites readers to grapple with state violence’s moral price. As Bergman writes, Israel’s story is a “slippery slope” the world, including the U.S., now navigates. For anyone seeking to understand intelligence, power, and the Middle East, Rise and Kill First is essential reading, a mirror to the shadows where nations wage their silent wars.