(By Quratulain Khalid)

I. Introduction

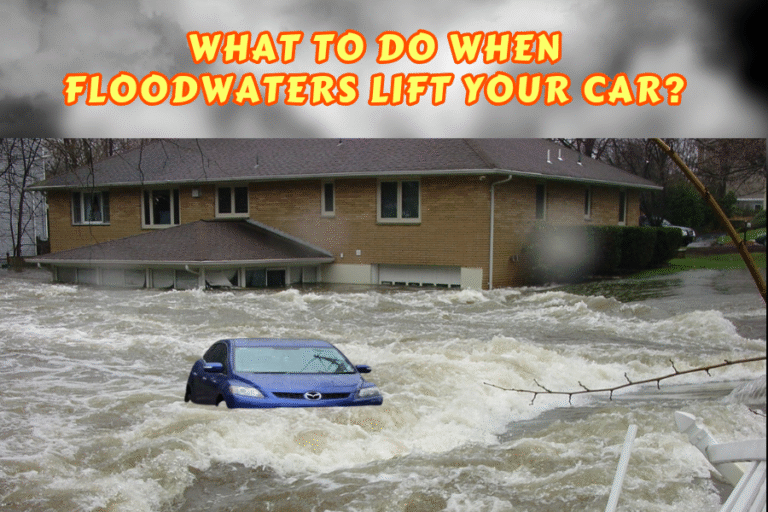

In July 2025, Pakistan faces relentless monsoon rains, marked by cloudbursts and urban flooding in major cities from Lahore to Rawalpindi and even in water-scarce regions like Chakwal, transforming streets into nullahs and exposing the nation’s fragile disaster management. This deluge, a natural gift, flows unharnessed into drains, rivers, and the Arabian Sea, wasting millions of acre-feet of fresh water annually—enough to meet the drinking needs of Pakistan’s 250 million people. The water crisis, with per capita availability nearing 860 cubic metres in 2025, is exacerbated by India’s suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty on 23 April 2025, following the Pahalgam attack, threatening Pakistan’s Chenab and Jhelum rivers flows critical for agriculture. While General Musharraf’s era saw small dams and check dams to capture runoff, two decades of inaction under democratic governments have left Pakistan vulnerable to water scarcity and India’s hydropolitical leverage—an asymmetric warfare tactic. This article explores rainwater harvesting, including rooftop systems and groundwater recharge, as a sustainable solution to mitigate flooding, bolster food security, and strengthen Pakistan’s resilience against the weaponization of river water by India.

II. Background: Pakistan’s Water Crisis and Rainwater Potential

Pakistan’s water crisis is a confluence of natural, geopolitical, and mismanagement challenges. The Indus River Basin, supplying over 80% of Pakistan’s irrigation and hydropower needs, is under strain from climate change, population growth, and inefficient water use. The Pakistan Council for Research in Water Resources (PCRWR) has warned that Pakistan could become water-scarce by 2025, with per capita water availability dropping below 1,000 cubic metres annually. Monsoon rains, contributing 60% of Pakistan’s rainfall (200–1,500 mm annually, concentrated in July–August), offer a vital resource, yet an estimated 29 million acre-feet of rainwater goes unutilized each year—enough to meet the drinking and household needs of Pakistan’s 250 million people. Urban areas like Karachi, Lahore, and now Chakwal face severe flooding due to poor drainage and lack of storage infrastructure, while rural areas suffer from waterlogging and salinity, rendering 53% of Sindh’s land agriculturally barren.

Historically, the Indus Valley Civilization (2600–1900 BCE) mastered water management through reservoirs and canals, a legacy that modern Pakistan has struggled to emulate. During General Musharraf’s tenure, initiatives like the Kachhi Canal and small check dams in Pothohar and Balochistan captured runoff for irrigation and groundwater recharge. However, since 2008, political disputes, notably over the Kalabagh Dam, and a focus on short-term relief over long-term infrastructure have stalled progress. India’s suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty, announced on 23 April 2025 after the Pahalgam attack, has intensified the crisis by threatening to divert water from the Chenab, Jhelum, and Indus rivers—allocated to Pakistan—through projects like the expanded Ranbir Canal and new dams (e.g., Pakal Dul, Ratle). This geopolitical manoeuvre, coupled with India’s cessation of hydrological data sharing, heightens flood risks and water uncertainty, making rainwater harvesting a strategic imperative.

III. The Current Challenge: Monsoon Flooding and Wasted Water

The 2025 monsoon season has brought devastation to Pakistan, with Chakwal—a semi-arid region in Punjab’s Pothohar Plateau—experiencing unprecedented flooding due to cloudbursts and consistent rainfall. Urban areas lack adequate drainage systems, leading to inundated roads, damaged homes, and disrupted livelihoods. In Chakwal, where annual rainfall averages 600–800 mm, the absence of harvesting infrastructure means that runoff flows into nullahs and rivers, contributing to downstream flooding in Punjab and Sindh before reaching the sea. Posts on social media platforms highlight public frustration, noting that Pakistan loses vast quantities of water annually due to insufficient storage, a sentiment echoed in the lack of dam construction since the Musharraf era.

India’s actions have compounded these challenges. On 4 May 2025, India reduced Chenab River flows by up to 90% at the Baglihar Dam, causing water levels at Pakistan’s Marala headworks to drop from 31,000 to 3,100 cusecs overnight, only partially recovering to 25,000 cusecs. This manipulation, alongside plans for a 113-km canal to divert water to Punjab, Haryana, and Rajasthan, threatens Pakistan’s kharif crop season, with water levels at Mangla and Tarbela dams nearing “dead levels.” Without India’s hydrological data, Pakistan faces heightened flood risks during the monsoon, as sudden dam releases could exacerbate downstream damage. Rainwater harvesting offers a critical solution to capture excess water, reduce flooding, and bolster water security against such geopolitical pressures.

IV. Rainwater Harvesting: A Time-Tested Solution

Rainwater harvesting involves collecting and storing rainwater from rooftops, landscapes, and catchments for domestic, agricultural, and industrial use. In Pakistan, this practice can mitigate urban flooding, recharge groundwater, and provide a supplementary water source. Techniques include:

- Rooftop Harvesting: Capturing rainwater from buildings using gutters and storage tanks. A 100-square-metre roof in Chakwal could collect up to 140,000 litres annually at 90% efficiency, suitable for household use after filtration.

- Diversion Systems: Channelling runoff through canals to agricultural fields or reservoirs, as seen in traditional Pothohar systems.

- Check Dams and Small Reservoirs: Low-cost structures to slow runoff, reduce soil erosion, and recharge aquifers, as implemented during the Musharraf era.

- Underground Tanks and Ponds: Storing rainwater in urban and rural areas to prevent flooding and ensure year-round availability.

The Earthquake Reconstruction and Regulation Authority (ERRA) and international partners have piloted projects demonstrating that small-scale harvesting can conserve significant water volumes. For instance, a single building with a 30×30-foot roof can harvest 150,000 litres annually, and a million such systems could rival one-quarter of Mangla Dam’s capacity. Despite these prospects, challenges like urbanization, uneven rainfall, and lack of maintenance hinder widespread adoption.

V. The Musharraf Era: A Missed Opportunity

During General Musharraf’s presidency (1999–2008), Pakistan invested in water conservation, constructing 58 small dams all over Pakistan. Notable dams are Mirani and Subakzai Dams in Balochistan and check dams in Pothohar to capture monsoon runoff. The Kachhi Canal project aimed to irrigate arid regions, while feasibility studies for the Kalabagh Dam sought to address storage needs. These efforts, though limited by inter-provincial disputes, demonstrated a commitment to water security. Since 2008, however, political gridlock and a focus on electoral optics—such as flood relief packages to seek votes in next elections – have sidelined infrastructure development. The absence of new dams, coupled with aging infrastructure like Mangla and Tarbela, has left Pakistan vulnerable to both floods and droughts, a situation worsened by India’s treaty suspension.

VI. Geopolitical Context: The Indus Waters Treaty Suspension

India’s suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty, a 65-year-old agreement brokered by the World Bank, marks a significant escalation in hydropolitics. The treaty allocates the Indus, Chenab, and Jhelum rivers to Pakistan, with India permitted to build run-of-the-river hydropower plants without significant storage. Following the 22 April 2025 Pahalgam attack, India halted data sharing on river flows and flood warnings, and began maintenance at Baglihar and Salal dams, reducing Chenab flows. Plans for new storage dams (e.g., Pakal Dul, 1,000 MW) and a 120-km Ranbir Canal expansion could divert 150 cubic metres per second from the Chenab, threatening Pakistan’s agriculture, which accounts for 24% of its economy. Pakistan has condemned this as an “act of war,” highlighting the treaty’s lack of a unilateral exit clause and exploring legal recourse through the World Bank or International Court of Justice. Rainwater harvesting can offset these losses by capturing monsoon water, reducing reliance on Indus flows and strengthening Pakistan’s resilience against asymmetric warfare tactics.

VII. Recommendations for Rainwater Harvesting in Pakistan

To harness monsoon rains and address water scarcity, Pakistan must adopt a multi-tiered rainwater harvesting strategy, tailored to urban and rural contexts:

- Urban Rainwater Harvesting Systems:

- Policy Incentives: Offer subsidies for households and businesses to install rooftop harvesting systems, including gutters, filters, and storage tanks, as piloted by Avenir Developments. A national campaign could target 1 million urban households, potentially harvesting 150 billion litres annually.

- Municipal Infrastructure: Develop urban ponds and underground tanks in cities like Peshawar, Rawalpindi, Chakwal, Lahore, and Karachi to store runoff, reducing flooding and recharging aquifers. Karachi’s 10 million residents, where 50% lack reliable water, could benefit significantly.

- Maintenance Protocols: Enforce regular cleaning of gutters and tanks to ensure water quality, addressing clogging issues noted in past projects.

- Rural and Agricultural Solutions:

- Revive Check Dams: Expand Musharraf-era check dams in Pothohar and Balochistan, using low-cost materials to capture runoff for irrigation and livestock. These can reduce waterlogging in Sindh, where 53% of land is saline.

- Diversion Canals: Construct channels to direct floodwater to agricultural fields, as practiced historically, to support crops like pulses and vegetables, reducing reliance on water-intensive rice and sugarcane.

- Community-Based Projects: Engage local communities in designing and maintaining small reservoirs, as recommended by the Climate Change Adaptation Project, to ensure sustainability.

- National Water Strategy:

- Integrated Policy Framework: Formulate a policy balancing groundwater recharge and surface water storage, prioritizing environmental flows to prevent desertification, as suggested by water experts.

- Public Awareness: Launch media campaigns to promote water conservation, highlighting successful pilots like ERRA’s 140,000-litre household systems.

- International Support: Seek funding from the World Bank and Asian Development Bank for rainwater harvesting infrastructure, leveraging Pakistan’s climate vulnerability status.

- Strategic Alignment with CPEC and Maritime Security:

- Protect CPEC Infrastructure: Use harvested water to support industrial zones along the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, ensuring water availability for economic growth despite India’s treaty suspension.

- Bolster Maritime Security: Invest in coastal rainwater harvesting to support port cities like Gwadar, reducing dependence on Indus flows and countering India’s hydropolitical pressures in asymmetric warfare.

- Legal and Diplomatic Measures:

- Pursue arbitration through the World Bank to challenge India’s treaty suspension, as it lacks legal grounds for unilateral withdrawal.

- Strengthen OSINT capabilities to monitor Indian dam activities, ensuring timely responses to water flow disruptions.

VIII. Conclusion

Pakistan’s 2025 monsoon season, marked by flooding in Chakwal and beyond, underscores the paradox of water abundance amidst scarcity. The failure to capture rainwater, coupled with India’s suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty, threatens Pakistan’s agriculture, economy, and strategic interests, including CPEC security and maritime security. While General Musharraf’s era laid a foundation with small dams and check dams, the past two decades have seen stagnation, with democratic governments prioritizing relief over infrastructure. Rainwater harvesting offers a sustainable solution to mitigate flooding, recharge groundwater, and reduce reliance on contested river flows. By implementing urban and rural harvesting systems, reviving check dams, and aligning with national priorities, Pakistan can transform the monsoon from a destructive force into a lifeline. The time to act is now—before the rains recede and the opportunity is lost to the sea.