(By Khalid Masood)

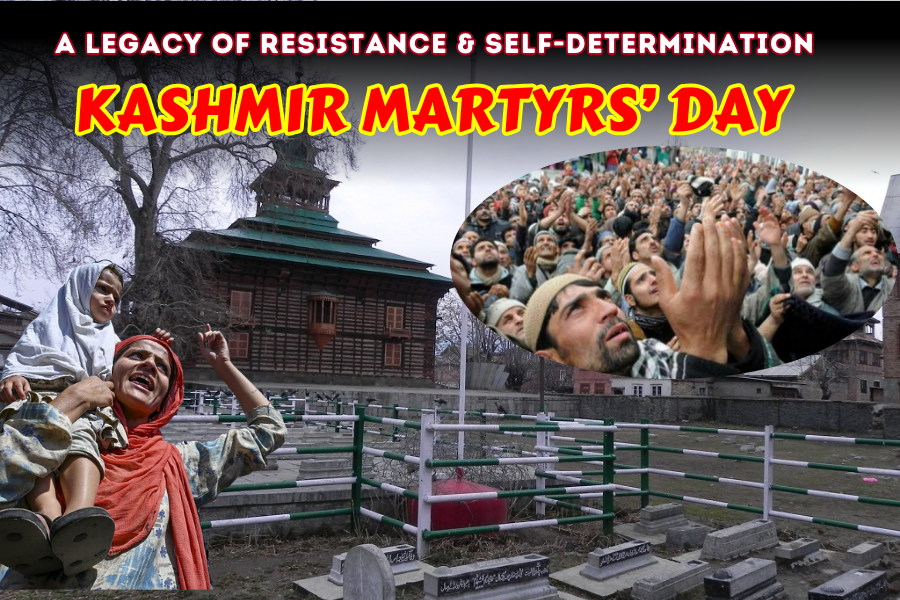

Every year on July 13, Kashmir Martyrs’ Day (Youm-e-Shuhada-e-Kashmir) is solemnly observed across Pakistan, Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK), and by Kashmiris worldwide to honor the 21 martyrs killed by Dogra forces outside Srinagar Central Jail in 1931. This day marks a pivotal moment in the Kashmiri struggle for freedom, symbolizing resistance against oppression and the enduring quest for self-determination. The Kashmir Dispute, rooted in the partition of the Indian Subcontinent in 1947, remains the oldest unresolved international conflict, fueled by India’s occupation of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K), in defiance of UN Security Council resolutions and the will of the Kashmiri people. This article explores the historical backdrop of Dogra rule, the significance of Martyrs’ Day, the partition’s impact, the Line of Control (LoC), human rights violations, and Pakistan’s unwavering commitment to the Kashmiri right to self-determination, while condemning India’s intransigence and calling for global accountability.

I. Historical Context: Dogra Rule and Kashmiri Oppression (1846–1947)

The Kashmir Dispute traces its origins to the Dogra rule (1846–1947), a period of systemic oppression for Kashmiri Muslims, who comprised 77% of J&K’s population. Established after the Treaty of Amritsar (1846), when the British sold Kashmir to Gulab Singh for 75 lakh rupees, the Dogra dynasty subjected Muslims to tyrannous treatment. Heavy taxation, forced labor, and discriminatory laws, such as capital punishment for cow slaughter, reduced Muslims to abject poverty, as noted by historian Prem Nath Bazaz. Kashmiri Muslims were denied basic rights, including access to education and government jobs, while Hindu Dogras enjoyed preferential treatment.

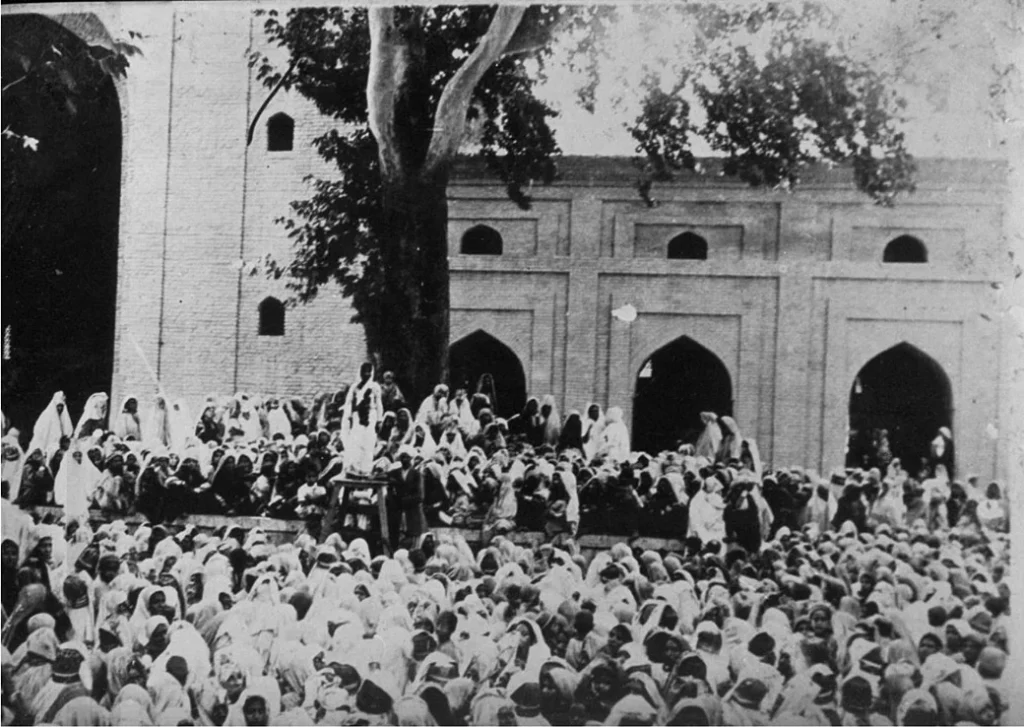

This oppression fueled resistance, culminating in the events of July 13, 1931, now commemorated as Kashmir Martyrs’ Day. The spark was lit on April 19, 1931, when the Dogra regime banned the Eid sermon in Jammu, igniting protests. The situation escalated when Dogra forces desecrated the Holy Quran in Jammu, prompting widespread outrage. On June 21, 1931, a gathering at Khanqah-e-Molla in Srinagar denounced this blasphemy, where Abdul Qadeer, a young Kashmiri, delivered a fiery speech against the Maharaja’s palace, shouting, “Destroy its every brick.” Accused of sedition, Qadeer’s trial was shifted to Srinagar Central Jail due to public unrest. On July 12, 1931, protests intensified, and on July 13, as thousands gathered outside the jail, a young Kashmiri began the Azan (call to prayer). Dogra soldiers shot him dead. One by one, 21 Kashmiris stepped forward to continue the Azan, each martyred in turn. Their bodies were paraded through Srinagar, sparking a complete strike and weeklong mourning, halting traffic from Srinagar to Rawalpindi and Jammu until July 26. The martyrs are buried in the Martyrs’ Graveyard at Khawaja Bazar, Srinagar, a sacred site for Kashmiri resistance.

This massacre galvanized the Kashmiri struggle, leading to the formation of the Muslim Conference (MC) in October 1932 under Sheikh Abdullah. On July 19, 1947, the MC passed a resolution to merge J&K with Pakistan, citing its Muslim-majority population, geographical proximity, and cultural-economic ties. This resolution reflected the Kashmiri aspiration for self-determination, a principle later enshrined in UN resolutions.

II. Partition of the Subcontinent and the Kashmir Dispute

The partition of British India in August 1947 into Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan set the stage for the Kashmir Dispute. Under the Indian Independence Act, princely states could accede to either dominion or remain independent, with rulers advised to consider geographical contiguity and population demographics. J&K, with a 77% Muslim population and economic ties to Pakistan via the Jhelum Valley route, was a natural candidate for Pakistan. However, Maharaja Hari Singh, a Hindu Dogra, delayed his decision, hoping to maintain independence.

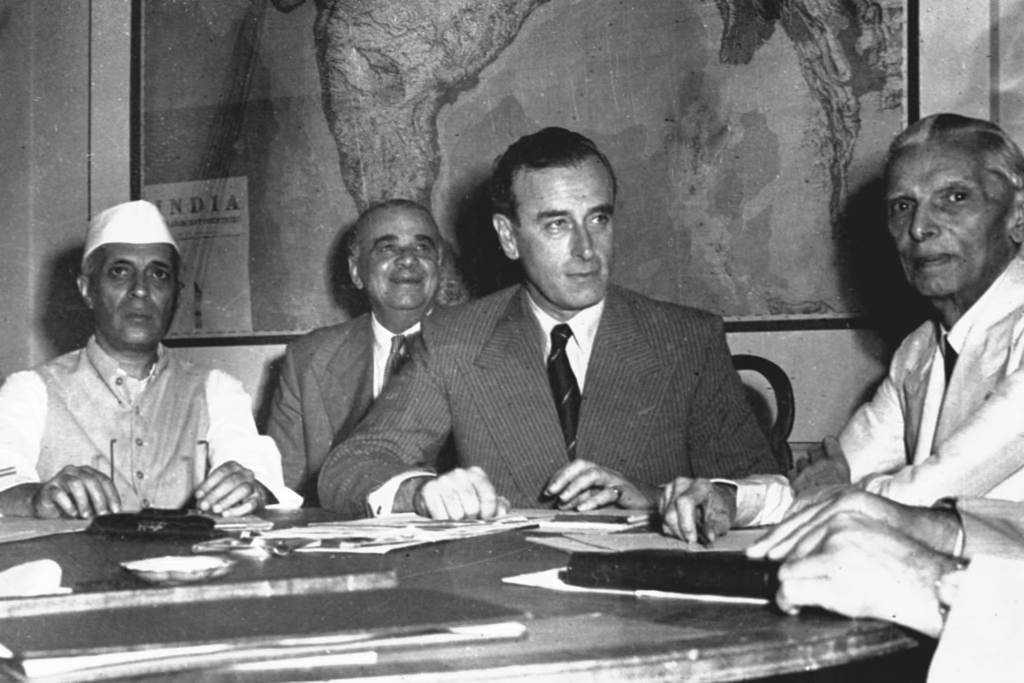

Instrument of Accession and Indian Occupation

In October 1947, Pashtun tribesmen from Pakistan entered Kashmir to support a local uprising against Dogra rule, prompted by reports of Muslim persecution. Fearing loss of control, Hari Singh signed the Instrument of Accession with India on October 26, 1947, allegedly under duress from Jawaharlal Nehru and Lord Mountbatten. Pakistan disputes the document’s legitimacy, citing doubts about its existence and the Maharaja’s lack of popular support. The United Nations recognizes Kashmir as a disputed territory, rejecting India’s claim of legal accession. On October 27, 1947, Indian forces airlifted into Srinagar, forcibly occupying J&K in violation of the partition’s principles.

The Radcliffe Boundary Award further complicated the dispute by granting Gurdaspur District, a Muslim-majority area, to India, providing a land route for Indian troops to access Kashmir. This decision, widely seen as biased, enabled India’s military intervention, undermining Kashmiri aspirations.

UN Involvement and Plebiscite Commitment

On January 1, 1948, India referred the dispute to the UN Security Council under Article 35 of the UN Charter, alleging Pakistani aggression. Pakistan countered that India’s accession was secured through “fraud and violence.” The UNSC passed Resolution 47 (April 21, 1948), outlining a three-step process for resolution: (1) Pakistan to withdraw its nationals, (2) India to reduce its forces to a minimum, and (3) a plebiscite to determine Kashmir’s future. The United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan (UNCIP), established under Resolution 39 (1948), reinforced this commitment, with resolutions on August 13, 1948, and January 5, 1949, emphasizing a free and impartial plebiscite. The ceasefire line, formalized by the Karachi Agreement (July 1949), became the Line of Control (LoC), dividing J&K into Indian-administered (55%, including Jammu, Kashmir Valley, and most of Ladakh) and Pakistan-administered (30%, Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan) regions, with China controlling 15% (Aksai Chin).

India’s refusal to implement the plebiscite, despite UN mandates, remains a core grievance. Pakistan upholds the UN resolutions, viewing them as binding, while India claims the Simla Agreement (July 2, 1972) superseded UN resolutions, mandating bilateral resolution. Pakistan rejects this, noting that Paragraph 6 of the Simla Agreement lists a “final settlement of Jammu and Kashmir” as unresolved, affirming the dispute’s international status.

III. Kashmir Martyrs’ Day: A Symbol of Resistance

Kashmir Martyrs’ Day commemorates the 21 martyrs of July 13, 1931, whose sacrifice ignited the Kashmiri struggle against Dogra tyranny and laid the foundation for the demand for self-determination. Observed across the LoC and by the Kashmiri diaspora, the day is a reminder of the cost of resistance. In Azad Kashmir and Pakistan, it is marked by prayers, rallies, and tributes, with posts on X reflecting its emotional weight: “22 brave souls stood against tyranny… their voices echo still” (@ArmaanMir25, July 13, 2025). In Indian-administered Kashmir, the day was an official holiday until 2019, when the revocation of Article 370 stripped J&K of its autonomy, further fueling resentment.

The 1931 massacre, as noted by Prem Nath Bazaz, was a “turning point in the political awakening” of Kashmiris, catalyzing the formation of the Muslim Conference and later the National Conference. It underscored the Kashmiri resolve to resist oppression, a spirit that persists in the face of India’s militarized control.

IV. Human Rights Violations in Indian-Administered Kashmir

India’s occupation of J&K has been marked by systemic human rights abuses, documented by Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, and UN reports (2018, 2019). The Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) grants Indian forces broad immunity, enabling extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances, and torture. A 2011 report by the Indian State Human Rights Commission confirmed over 2,000 unmarked graves near the LoC, suggesting mass atrocities. The 2019 revocation of Article 370, which ended J&K’s semi-autonomous status, was accompanied by a security lockdown, media blackout, and mass detentions, with 13,000 teenagers reportedly detained, as per a 2019 fact-finding report by Indian activists.

Kashmiris face curfews, communication blackouts, and restrictions on freedom of expression, with local media censored through government-controlled advertising, as per Human Rights Watch (2020). The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights has criticized India’s policies, urging respect for Kashmiri rights. Pakistan’s stance, articulated by Imran Khan at the UN General Assembly (2019), warns of a “bloodbath” if the oppression continues, a sentiment celebrated by some Kashmiris with firecrackers.

V. Pakistan’s Commitment to Self-Determination

Pakistan views Kashmir as its jugular vein, a core political issue tied to the two-nation theory that justified the Subcontinent’s partition. The National Assembly of Pakistan emphasizes that the dispute is not merely territorial but a human issue affecting 13 million Kashmiris. Pakistan upholds the UN resolutions advocating a plebiscite, rejecting India’s claim that elections in Indian-administered Kashmir (e.g., 0.2% turnout in 1989) constitute self-determination. The Simla Agreement does not negate these resolutions, as it explicitly lists J&K’s final status as unresolved.

Pakistan’s diplomatic efforts, including raising the issue at the UN General Assembly and through the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), underscore its commitment. In 2019, Turkey’s President Erdogan and US President Donald Trump supported dialogue, with Trump offering mediation, though India rejected external involvement. Pakistan’s military restraint, as seen in the 2003 ceasefire and its response to Operation Sindoor, reflects a desire for peaceful resolution, despite India’s provocations.

VI. India’s Intransigence and Global Implications

India’s refusal to honor UNSC Resolution 47 and subsequent resolutions reflects a pattern of dishonesty, as admitted by V.P. Menon in 1964, who acknowledged India’s insincerity on the plebiscite. Nehru’s resistance, followed by Indira Gandhi’s 1975 accord with Sheikh Abdullah, eroded Kashmiri autonomy, while Modi’s 2019 revocation of Article 370 entrenched India’s control, allowing outsiders to buy land and altering the Muslim demographic. Pandit Govind Ballabh Pant (1956) and Rajnath Singh (2017) dismissed plebiscite demands, with Singh provocatively suggesting a referendum in Pakistan instead.

The UN Security Council’s inaction since 1971, coupled with India’s claim that the Simla Agreement renders UN resolutions obsolete, has emboldened India’s militarization of Kashmir, making it one of the most militarized zones globally. The UNMOGIP, established in 1951, continues to monitor the LoC but lacks enforcement power. The international community, except India, recognizes Kashmir as a disputed territory, yet geopolitical alliances, particularly the US-India strategic partnership, hinder UN intervention.

VII. Recommendations for Resolution

To honor the martyrs of 1931 and resolve the Kashmir Dispute, the following steps are imperative:

- Implement UN Resolutions: The international community must pressure India to honor Resolution 47, enabling a plebiscite under UN supervision to ensure Kashmiri self-determination.

- De-escalate Tensions: India and Pakistan should reinstate the 2003 ceasefire, with UNMOGIP oversight, to reduce LoC violence, as seen in Operation Sindoor (2025).

- Address Human Rights: India must repeal AFSPA, release political prisoners, and allow UN observers to investigate abuses, as urged by OHCHR reports (2018, 2019).

- Promote Dialogue: Third-party mediation, as offered by Trump (2019 & 2025), could facilitate India-Pakistan talks, including Kashmiri representatives.

- Support Kashmiri Voices: Pakistan should amplify Kashmiri leaders like those in the All Parties Hurriyat Conference, ensuring their inclusion in negotiations.

VIII. Conclusion

Kashmir Martyrs’ Day is a poignant reminder of the 21 heroes who, on July 13, 1931, sacrificed their lives for freedom and dignity, igniting a struggle that endures nearly a century later. The Kashmir Dispute, born from the partition of 1947 and India’s illegal occupation, remains a human tragedy, with 13 million Kashmiris denied their right to self-determination. Pakistan’s steadfast support for UN resolutions and the Kashmiri cause reflects its commitment to justice, while India’s militarization and human rights abuses betray the principles of the UN Charter. The international community must act to enforce the plebiscite, end India’s oppression, and honor the martyrs’ legacy. As social media post proclaim today on Twitter, “Their voices echo still”, urging a world that has too long ignored Kashmir’s cry for freedom.