(By Quratulain Khalid)

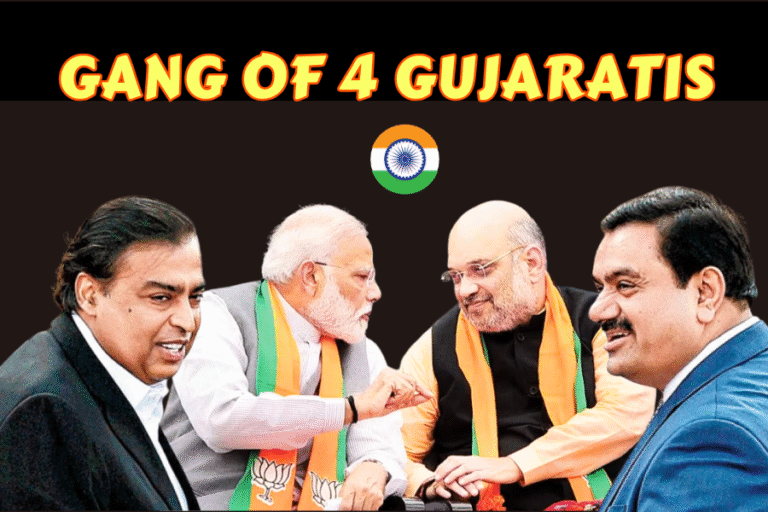

For decades, Bollywood has been India’s most potent instrument of soft power, beaming its songs, stars, and stories to more than three billion people worldwide. Yet this same industry has systematically weaponised its reach to demonise Pakistan, portraying its people, state, and institutions as the root of all evil on the subcontinent. The latest casualty of this pattern is Dhurandhar (2025), a high-octane spy thriller directed by Aditya Dhar that was banned across six Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries – Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates – for its blatant anti-Pakistan propaganda.

This is not just another film controversy. It is the strongest collective rebuke yet from the Arab world to India’s state-backed cinematic hate campaign against Pakistan.

The Film That Crossed the Red Line

Released in October 2025, Dhurandhar stars Ranveer Singh as an undercover RAW officer embedded in Karachi’s Lyari neighbourhood during the height of the gang wars of the late 2000s and early 2010s. The film openly borrows real-life figures – the fearless police officer Chaudhry Aslam Khan and gangster Rehman Dakait – but twists their stories into a narrative that paints Pakistan’s police and society as complicit in terrorism while glorifying Indian intelligence as the sole saviour.

Aditya Dhar, the director, has built his career on such themes. His previous blockbusters Uri: The Surgical Strike (2019) and Article 370 (2024) turned disputed military and political events into chest-thumping propaganda that many critics in India itself labelled “government-approved fan fiction”. Persistent rumours – never officially denied – claim that sections of Indian intelligence quietly encourage, and sometimes even help finance, such projects to shape domestic and global opinion.

Despite the controversy, Dhurandhar stormed past ₹300 crore at the Indian box office, proving once again that hatred sells.

A Long History of Cinematic Hostility

The negative stereotyping of Pakistan in Bollywood is not new, but it has intensified dramatically since 2014:

- Border (1997) and LOC Kargil (2003) established the template of the treacherous Pakistani soldier.

- Gadar: Ek Prem Katha (2001) turned the Partition into a one-sided morality play.

- Post-2016, the industry shifted into overdrive: Phantom (2015), Baby (2015), Uri (2019), Shershaah (2021), The Kashmir Files (2022), Fighter (2024), and Article 370 (2024) all recycle the same tropes – Pakistan and the ISI as the eternal sponsors of terrorism, Kashmiris as helpless until rescued by India, and any Pakistani character either a fanatic or a duplicitous villain.

Academic studies and media surveys confirm the impact. A 2021 survey by Lokniti-CSDS found that Indians who regularly watch Bollywood war films are 40 % more likely to hold strongly negative views of Pakistan than non-viewers. Among the Indian diaspora in the West, these films have become the primary lens through which an entire generation understands the Kashmir conflict and India–Pakistan relations.

The Gulf Says “Enough”

The unified GCC ban on Dhurandhar is unprecedented in scale and coordination. While individual Gulf countries have occasionally blocked Indian films before (Fighter in 2024 and parts of Tiger 3 in 2023), never have all six states acted together against a single Bollywood release.

The official reason cited by censorship boards: “incitement of hatred and distortion of a friendly nation’s image”. Behind the diplomatic language lies a clearer message:

- Economic and strategic reality – More than eight million Pakistani expatriates live and work in the Gulf, sending home over $8 billion annually in remittances. Pakistan’s military training missions, counter-terrorism cooperation, and growing defence exports (notably JF-17 aircraft and drones) have deepened ties with Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar.

- Rejection of divisive propaganda – Gulf governments, already battling extremist narratives at home, refuse to allow imported fiction that stokes sectarian or national hatred.

- A quiet warning to New Delhi – India’s $100-billion-plus trade with the GCC and its reliance on Gulf energy and investment do not grant it immunity to peddle one-sided hatred.

A Message India Cannot Afford to Ignore

By banning Dhurandhar, the Gulf states have told India three things in unmistakable terms:

- Soft power that relies on demonising a brotherly Muslim nation will face limits.

- The era of unchallenged Bollywood propaganda in the Arab world is over.

- Balanced relations with both India and Pakistan are non-negotiable; picking sides through cinema is unacceptable.

This is a diplomatic slap delivered through cinema screens, and it stings precisely because Bollywood has always taken its Gulf market for granted.

Time for Pakistan to Seize the Narrative

The ban offers Pakistan a golden opportunity. For too long, Islamabad has reacted defensively to Bollywood’s onslaught. Now the world is listening. Pakistani filmmakers must tell their own stories – the real heroism of Chaudhry Aslam, the complexity of Lyari’s social fabric, the sacrifices of soldiers and civilians in the war against terrorism – with the same production values and global ambition that Bollywood deploys.

Platforms like Netflix, Amazon, and Shahid are hungry for South Asian content. A single powerful, authentic Pakistani counter-narrative could do more for hearts and minds than a hundred press releases.

Conclusion

Bollywood will continue making films that glorify India and vilify Pakistan as long as they remain profitable at home. But the Gulf ban on Dhurandhar proves that the rest of the world no longer has to accept this toxic export.

When six influential Arab nations stand together to say “this hatred has no place on our screens”, they are not just protecting Pakistan’s image – they are defending the very idea that cinema should unite rather than divide.

The message from Manama to Muscat, from Riyadh to Abu Dhabi is crystal clear: propaganda disguised as entertainment will be treated as the poison it is.

Pakistan has won a battle in the war of narratives. The next move belongs to its storytellers.