(By Khalid Masood)

Greenland, the world’s largest island and a self-governing autonomous territory within the Kingdom of Denmark, has emerged as one of the most volatile flashpoints in contemporary geopolitics. As of mid-January 2026, U.S. President Donald Trump has escalated his long-standing interest into overt threats, repeatedly stating that the United States will acquire or control Greenland “one way or the other“—explicitly refusing to rule out military force. In response, Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen has described the moment as a “fateful” crossroads for Denmark and warned that any U.S. attack on Greenland, a NATO ally territory, would mean “the end of NATO” and the post-World War II security order.

This crisis is not merely rhetorical bluster. It revives century-old American strategic calculations, now intensified by climate-driven Arctic changes, vast untapped critical mineral reserves, and rising competition with Russia and China. The standoff tests the resilience of transatlantic alliances, the sanctity of sovereignty in international law, and the future of Arctic governance in a warming world. With Secretary of State Marco Rubio scheduled to meet Danish and Greenlandic officials in the coming days (around January 14–15, 2026), the outcome could either de-escalate through diplomacy or deepen fractures in NATO.

Geographical and Environmental Context

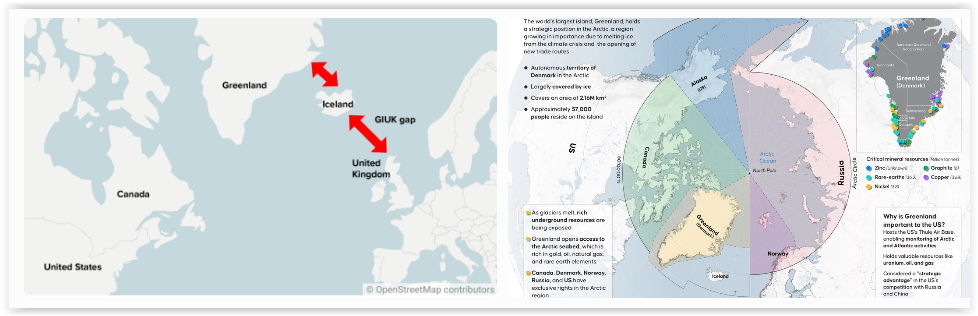

Greenland covers approximately 2.166 million square kilometers—larger than Mexico but with only about 57,000 inhabitants, predominantly Inuit. Roughly 80% is covered by an ice sheet up to 3 km thick, making it the second-largest ice mass after Antarctica. Its capital, Nuuk, exemplifies the blend of traditional Inuit life with modern infrastructure amid stunning fjords and rugged terrain.

Climate change accelerates the transformation: Greenland’s ice sheet loses around 270 billion tonnes annually, thinning rapidly and exposing vast mineral deposits while opening navigable Arctic passages like the Northwest Passage and Northern Sea Route. These shifts reduce transit times between Asia and Europe/Atlantic ports, potentially reshaping global trade but also heightening environmental risks, including rising sea levels, disrupted ecosystems, and threats to indigenous livelihoods dependent on sea ice for hunting and fishing.

Historical U.S. Interest in Greenland

U.S. fascination with Greenland predates the current crisis by over 150 years. In 1867, following the Alaska Purchase, Secretary of State William H. Seward explored acquiring Greenland (and Iceland) from Denmark, viewing them as extensions of American Arctic expansion. A positive Coast Survey report highlighted resources like fish, game, and minerals, but congressional disinterest and Danish reluctance halted progress.

In 1910, under President William Howard Taft, diplomats proposed land swaps or concessions, but Denmark rejected them. World War II marked a turning point: After Nazi Germany’s 1940 occupation of Denmark, the U.S. invoked the Monroe Doctrine for defensive occupation, signing a 1941 agreement with Danish representatives to establish bases and prevent German exploitation.

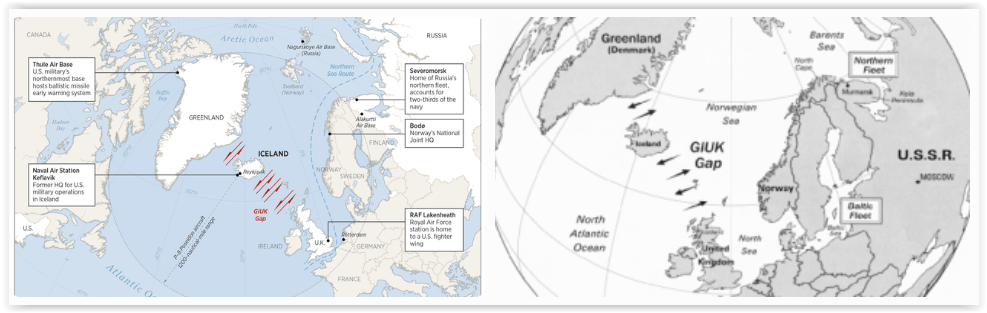

The Cold War intensified efforts. In 1946, President Harry Truman offered Denmark $100 million in gold (equivalent to billions today) to purchase Greenland outright, deeming it “indispensable” for defense against Soviet threats. Denmark refused, leading to the 1951 Defense Agreement granting broad U.S. military rights, including Pituffik Space Base (formerly Thule) for missile warning and surveillance.

Later discussions (e.g., 1955) fizzled. Previous administrations prioritized alliance stability (Denmark joined NATO in 1949) and existing access over risky ownership, avoiding breaches of post-WWII norms against territorial conquest. Trump’s revival—first in 2019 as a “real estate deal,” now aggressively in 2025–2026—breaks this restraint, emboldened by actions like the Venezuela intervention.

Strategic and Military Importance

Greenland’s location dominates the GIUK Gap (Greenland-Iceland-United Kingdom), a critical North Atlantic chokepoint for monitoring submarine and naval traffic between the Arctic and Atlantic. It forms part of the shortest ballistic missile trajectory from Russia to the U.S., making Pituffik essential for early warning, missile defense, and space surveillance.

For the U.S., full control would provide an “unsinkable aircraft carrier,” deterring Russian militarization (Arctic bases, icebreakers) and Chinese “Polar Silk Road” ambitions. Trump frames it as a “national security priority” to prevent rival dominance amid melting ice and new routes.

Europe/NATO views emphasize collective security: Greenland bolsters the northern flank through shared monitoring and exercises. Unilateral U.S. action risks invoking Article 5 obligations, fracturing unity, and benefiting adversaries. NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte has avoided direct criticism of Trump, praising defense spending pushes while stressing joint Arctic enhancements.

Economic and Resource Value

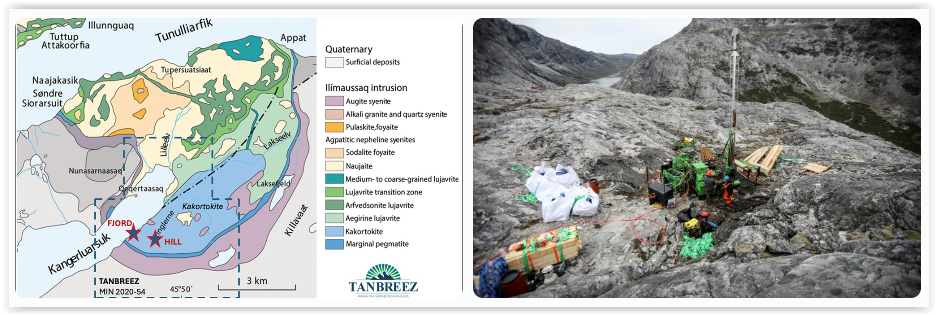

Greenland holds immense critical mineral potential, ranking eighth globally in rare earth reserves (~1.5 million metric tons). Key deposits include Kvanefjeld (third-largest known land REE deposit, with heavy rare earths and uranium) and Tanbreez (potentially larger, high heavy REE concentration, exploitation licensed).

Greenland’s Internal Dynamics and Sovereignty

These resources—neodymium, dysprosium, yttrium, plus graphite, lithium, zinc—are vital for EVs, renewables, defense tech, and electronics, reducing reliance on China’s ~65–69% processing dominance. Melting ice improves access, but challenges persist: harsh logistics, infrastructure deficits, environmental regulations, and uranium-related waste issues delay production (Tanbreez potentially 2027–2030).

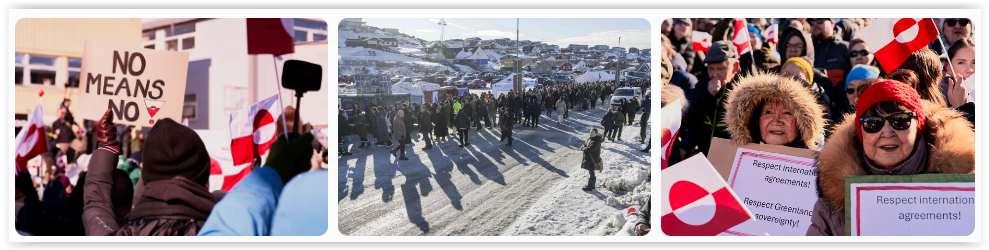

Since 2009 self-rule, Greenland pursues gradual independence, funded by Danish subsidies (~€530 million/year). Polls show 85%+ rejection of U.S. takeover; leaders prioritize self-determination. United statements affirm: “We don’t want to be Americans… The future of Greenland must be decided by Greenlanders.”

Indigenous Inuit concerns focus on cultural preservation, environmental protection, and economic benefits. Danish leaders reject threats, emphasizing NATO defense and sovereignty.

The 2026 Crisis: Timeline and Implications

The Greenland crisis of early 2026 stands as one of the gravest challenges to NATO’s unity since its inception in 1949. Revived from Donald Trump’s 2019 “large real estate deal” comments during his first term, the issue exploded into explicit threats of acquisition “one way or the other”—including military force—following the U.S. military raid in Venezuela that captured Nicolás Maduro and his wife in late December 2025/early January 2026. This operation emboldened the Trump administration, with aides framing Greenland as the next “national security imperative” to secure Arctic dominance against Russia and China. The rapid escalation shifted from diplomatic hints to public confrontations, drawing sharp rebukes from Denmark, Greenland, and European allies.

The timeline unfolded intensely over the first two weeks of January 2026:

- Early January (January 1–4, post-Venezuela raid): Trump’s threats surged immediately after the Venezuela operation. White House officials, including deputy chief of staff Stephen Miller, amplified claims that Greenland was vulnerable to Russian and Chinese influence. Trump labeled it a “national security imperative,” tying it to broader Arctic strategy. Denmark’s Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen issued early warnings that the U.S. had “no right to annex” the territory and urged Trump to “stop the threats.” Greenland’s Prime Minister Jens-Frederik Nielsen condemned the rhetoric as “fantasies about annexation” and “utterly unacceptable,” declaring “enough is enough” and insisting Greenland’s future must be decided by its people.

- January 5–9: Rhetoric reached a fever pitch. On January 5, Frederiksen delivered forceful interviews with Danish broadcasters (DR and TV2), warning that a U.S. attack on Greenland would mean “the end of NATO” and the post-World War II security order. She emphasized that threats “should be taken seriously” and reiterated Greenland “belongs to its people.” Nielsen echoed this on social media and in statements, rejecting any U.S. takeover. Trump countered aggressively: On January 9, during a White House meeting with oil and gas executives, he declared the U.S. would “do something on Greenland whether they like it or not,” preferring the “easy way” (a negotiated deal) but ready for the “hard way.” He ridiculed Denmark’s defenses, claimed Greenland was “full of Chinese and Russian ships,” and argued the U.S. must act to prevent rival dominance. White House discussions reportedly explored options like purchasing the territory, direct payments to Greenlanders ($10,000–$100,000 per person to encourage secession), or military intervention—though Secretary of State Marco Rubio and others stressed a preference for buying over invading.

- January 7–8: Rubio briefed Congress in classified sessions, indicating the administration aimed to buy Greenland rather than invade, while not ruling out force. Denmark’s Foreign Minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen and Greenland’s Foreign Minister Vivian Motzfeldt requested an urgent meeting with Rubio to “add nuance” and shift from “shouting match” to dialogue. European solidarity solidified: Leaders from France, Germany, the UK, Italy, Poland, Spain, and others issued a joint statement affirming that “Greenland belongs to its people” and Arctic security must remain collective through NATO, not unilateral U.S. action.

- January 11–12: Frederiksen described the situation as a “fateful” or “decisive” moment for Denmark in domestic debates and media appearances, accusing the U.S. of potentially abandoning NATO commitments. Greenland’s political parties issued a rare unified cross-partisan statement: “We do not want to be Americans… The future of Greenland must be decided by Greenlanders.” Polls showed over 85% of Greenlanders rejecting U.S. annexation. European allies continued rallying, with discussions on reinforcing Arctic security (e.g., operations modeled on Baltic Sentry or Eastern Sentry for surveillance and patrols) to demonstrate commitment without escalation.

- Ongoing (as of January 13, 2026): Rubio confirmed he would meet Danish and Greenlandic officials in the coming days (likely January 14–15) to address the crisis. NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte avoided direct criticism of Trump, praising defense spending efforts while framing Arctic priorities as shared alliance concerns. Behind closed doors, European diplomats explore collective responses, including potential EU mutual assistance mechanisms or enhanced NATO northern flank operations, amid fears that unresolved tensions could irreparably damage transatlantic unity.

Implications

The crisis poses multifaceted risks:

- NATO Credibility and Cohesion: Frederiksen’s warnings—that U.S. aggression against an ally territory would destroy Article 5 mutual defense and end the alliance—resonate widely. A forced takeover would undermine the principle that NATO members do not threaten one another, potentially triggering Article 4 consultations or even EU mutual assistance clauses. Transatlantic trust, strained by Trump’s past alliance critiques, could collapse, weakening deterrence against Russia in Europe and Ukraine support.

- Arctic Fracture Favoring Rivals: Russia (with extensive Arctic bases and icebreakers) and China (pursuing a “Polar Silk Road” through investments and infrastructure) benefit from NATO disarray. Beijing dismissed U.S. claims as an “excuse” for territorial ambitions. A divided West accelerates rival influence over emerging shipping routes and resource extraction.

- Precedents for Coercion: The episode risks normalizing major-power territorial grabs under “security” pretexts, echoing Cold War Soviet interventions in allied states and violating UN Charter sovereignty norms.

- Economic and Diplomatic Fallout: Greenland’s independence path (supported across parties) could accelerate under pressure, but with trade-offs between U.S. economic promises and Danish subsidies (~€530 million/year). EU integration proposals (e.g., phased membership by 2026–2027 with investments in infrastructure and critical minerals) emerge as countermeasures to counter U.S. leverage and preserve ties.

Trump and Frederiksen embody the divide: Trump’s “America First” unilateralism versus Frederiksen’s defense of alliance solidarity and sovereignty. The rhetoric has moved from bluster to active diplomacy, with Rubio’s meetings now pivotal.

Possible Scenarios and Future Outlook

Several plausible paths forward carry significant consequences:

- Diplomatic Resolution (Most Probable Short-Term Outcome): Negotiations expand U.S. basing and mining rights under the existing 1951 Defense Agreement, combined with joint U.S.-EU investments in infrastructure, sustainable mineral extraction, and economic incentives for Greenland. This allows Trump to claim a “win” on security while preserving alliance cohesion. European proposals for enhanced Arctic patrols (modeled on Baltic/Eastern Sentry) could reassure Washington without sovereignty transfer.

- Stalemate or Selective Escalation: Trump applies targeted pressure—sanctions, direct outreach to Greenland bypassing Copenhagen, or symbolic military posturing at Pituffik. Full-scale invasion remains highly unlikely due to catastrophic NATO fallout, domestic U.S. opposition (e.g., congressional resistance), and logistical challenges—but sustained rhetoric prolongs uncertainty, erodes alliances, and rattles markets.

- Greenland’s Accelerated Independence Path: External pressure hastens internal debates on full sovereignty. Greenland could pursue phased EU membership, deeper EU funding for sustainable development and critical minerals, or diversified partnerships (e.g., with Canada or Nordic allies). This preserves Inuit culture and welfare models while reducing vulnerability to coercion. Strong local opposition to U.S. annexation bolsters this trajectory.

Long-Term Outlook

The Arctic’s evolving landscape—driven by climate change exposing minerals and routes—demands robust multilateral governance via NATO, the Arctic Council, or new frameworks balancing security, resource access, and environmental protection. Unresolved, the crisis could erode NATO’s credibility, embolden adversaries, and push Europe toward greater strategic autonomy (e.g., independent Arctic capabilities). Diplomacy respecting sovereignty offers the most stable path; coercion risks broader instability and a fractured Western order.

Ultimately, this episode highlights a multipolar world’s tensions: Unilateralism versus alliance norms. As Rubio’s meetings loom, the Arctic’s future—and NATO’s endurance—remains delicately poised.