(By Khalid Masood)

The surrender of Pakistani forces in Dhaka on December 16, 1971, marked the end of a united Pakistan and the birth of Bangladesh. This event, often described as one of the darkest chapters in Pakistan’s history, stemmed from deep-seated grievances in East Pakistan that transformed initial enthusiasm for Pakistan among Bengalis into demands for autonomy and, ultimately, independence. Bengalis had been at the forefront of the Pakistan Movement, with leaders like A.K. Fazlul Huq presenting the historic Lahore Resolution in 1940. Yet, over the next two decades, a series of policies and attitudes from the central government in West Pakistan alienated the majority population in the East, sowing seeds of disillusionment.

The Language Controversy: Seeds of Discontent During Jinnah’s Lifetime

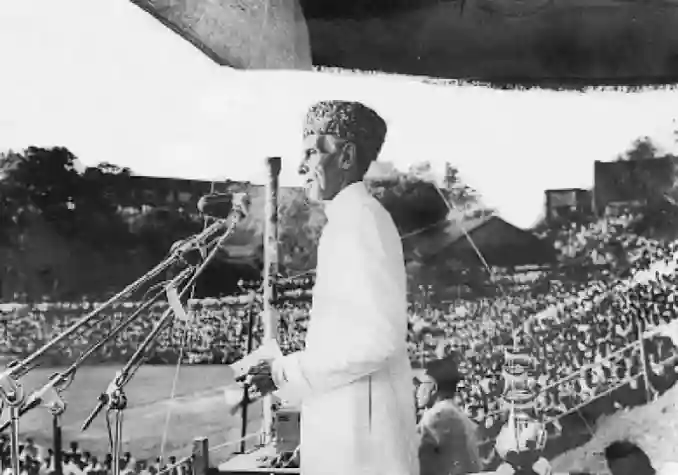

The language issue emerged almost immediately after Pakistan’s creation, highlighting cultural differences between the Urdu-speaking West and Bengali-speaking East. In March 1948, during his only visit to East Pakistan, Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah declared in Dhaka that Urdu would be the sole state language of Pakistan. He reiterated this at Dhaka University’s Curzon Hall, stating, “Urdu and Urdu alone” would embody the spirit of the nation, dismissing opposition as the work of “enemies of Pakistan.” Protests erupted, with crowds shouting “No!” in response.

This stance was seen by many Bengalis as an imposition, given that Bengali was spoken by over 56% of Pakistan’s population. Early protests in 1948 against removing Bengali script from currency and stamps escalated into the Bengali Language Movement. By 1952, demands for Bengali’s recognition as a co-official language led to widespread demonstrations. On February 21, 1952 (now International Mother Language Day), police fired on protesters in Dhaka, killing several students. This violence galvanized Bengali identity, fostering a sense of cultural suppression and marking the beginning of organized resistance against perceived West Pakistani dominance.

The 1952 Language Riots and Shifting Sentiments

The 1952 riots profoundly impacted Bengali hearts and minds. The killings unified students, intellectuals, and the masses, transforming linguistic demands into broader calls for equality. It strengthened support for parties like the Awami League, founded as an alternative to the Muslim League, and laid the groundwork for Bengali nationalism. While Bengali was eventually recognized as a state language in 1956, the damage was done—the movement highlighted West Pakistan’s reluctance to accommodate East Pakistan’s majority culture.

Sidelining of Bengali Leaders and Early Political Marginalization

The systematic marginalization of Bengali leaders in the early years of Pakistan played a pivotal role in alienating East Pakistan’s majority population. Despite their significant contributions to the Pakistan Movement, prominent Bengali figures were repeatedly sidelined, dismissed, or humiliated by the West Pakistani-dominated central establishment, which consolidated power among non-Bengali elites. This pattern of political subjugation sent a clear message of distrust and deepened feelings of resentment, as East Pakistan’s voices were consistently ignored in national decision-making.

A.K. Fazlul Huq: The Betrayed Pioneer A.K. Fazlul Huq, known as Sher-e-Bangla, who moved the historic Lahore Resolution in 1940 envisioning autonomous Muslim-majority regions, was gradually sidelined after Pakistan’s formation despite his pivotal role in the independence struggle. A stark example occurred in 1954 when his Krishak Sramik Party, in coalition as the United Front (Jugto Front), secured a landslide victory in the East Bengal provincial elections, winning 223 out of 309 seats. Fazlul Huq became Chief Minister of East Bengal, but the central government swiftly imposed Governor’s Rule, dismissed his ministry within weeks, and later arrested and jailed him on various charges. This heavy-handed intervention underscored the West Pakistani elite’s reluctance to allow genuine Bengali political power.

Khawaja Nazimuddin: The Dismissal of a Loyalist Khawaja Nazimuddin, a devout aristocratic Bengali leader from Dhaka’s Nawab family and one of Quaid-e-Azam’s most trusted companions, served as Pakistan’s second Prime Minister from 1951 to 1953. Despite enjoying parliamentary confidence and recently passing the budget, his government was abruptly dismissed on 17 April 1953 by Governor-General Malik Ghulam Muhammad, a West Pakistani bureaucrat, citing vague “administrative failure” amid the anti-Ahmadi riots in Lahore. Widely viewed as unconstitutional and motivated by Nazimuddin’s refusal to compromise East Pakistan’s interests, the move was celebrated by the Punjab-dominated bureaucracy, which portrayed him as weak. Deeply humiliated, Nazimuddin withdrew from politics, symbolizing how even loyal Bengalis were discarded.

Mohammad Ali Bogra: The Unceremonious Ouster of a Diplomat Mohammad Ali Bogra, a soft-spoken Bengali diplomat from Bogra district, was recalled from his US ambassadorship in 1953 to replace Nazimuddin as Prime Minister. Best known for the “Bogra Formula” aiming for balanced representation, he sought national unity but was forced to resign in August 1955 by acting Governor-General Iskander Mirza (aligned with West Pakistani elites) over disputes on the One Unit scheme and resource allocation. His advocacy for East Pakistan made him inconvenient; West Pakistani leaders treated him condescendingly as a temporary figurehead. Sidelined to minor diplomatic roles thereafter, his ouster reinforced Bengali convictions that no leader from the East would be permitted lasting authority.

Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy: The Victim of Vindictive Victimization Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, the charismatic leader who had served as Prime Minister of undivided Bengal, became Pakistan’s Prime Minister in 1956, championing autonomy and economic justice for East Pakistan. His refusal to accept the One Unit plan provoked fierce opposition, leading President Iskander Mirza to engineer his resignation in October 1957. Under Ayub Khan’s 1958 martial law, Suhrawardy endured arrests, house arrest, and surveillance, branded a traitor by West Pakistani leaders. His mysterious death in Beirut in 1963—officially a heart attack but widely suspected as orchestrated—marked the extreme lengths to which the establishment would go to eliminate strong Bengali challengers.

Perceptions of External Influence and Internal Divisions

Residual Hindu influence among Bengali educators and professors contributed to anti-West Pakistan sentiments among Bengali college and university students, particularly targeting Punjabis as symbols of central authority. Hindu teachers, who remained influential in education due to historical advantages under British rule, were accused of fostering separatism. However, the movement was broadly supported across religious lines, driven by genuine grievances over discrimination.

Military and Security Disparities

During the 1965 Indo-Pak War, East Pakistan’s defences were notably weak—one infantry division with limited battalions—despite its long border with India. No major Indian attack occurred there, but the vulnerability exposed neglect, reinforcing feelings of second-class status.

Economic disparities compounded this: East Pakistan generated much of Pakistan’s foreign exchange through jute exports but received disproportionately less development funding (around 20-36% in early plans despite 55-60% population share). Per capita income gaps widened, with West Pakistan benefiting more from aid and investment.

West Pakistani civil and military elites were often perceived as degrading Bengalis, viewing them as culturally inferior or less martial. This attitude fueled resentment.

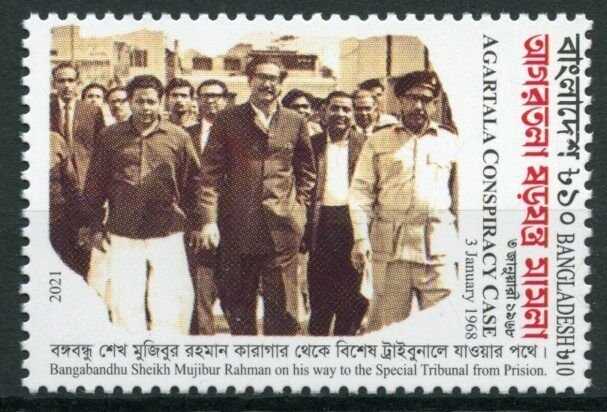

The Agartala Conspiracy and Escalation

In 1968, the Pakistani government charged Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and others in the Agartala Conspiracy Case, alleging meetings with Indian officials (including RAW) in Agartala for armed rebellion, funded and supported by India. The case was withdrawn amid mass protests in 1969, boosting Mujib’s popularity. Later confessions by some accused confirmed contacts seeking Indian aid, while others viewed it as a fabricated ploy to discredit Bengali leaders. This episode highlighted intelligence failures and deepened mistrust.

Inadequate Military Deployment and the Overwhelming Odds in 1971

A critical factor exacerbating East Pakistan’s vulnerability was the chronically inadequate number of troops stationed there. For decades, the bulk of Pakistan’s military strength was concentrated in the West, leaving East Pakistan defended by only one division (around 16,000 troops) before the crisis escalated. Even at the height of the 1971 conflict, reliable estimates place the effective combat strength of Pakistani forces at approximately 35,000-45,000 soldiers (primarily from three infantry divisions, with support elements), isolated geographically with no possibility of reinforcement by sea or air due to Indian naval blockade and air superiority.

These forces faced overwhelming opposition: an Indian Army commitment of around 250,000-300,000 troops in the eastern theater, supported by superior armor, artillery, and air power, alongside an estimated 75,000-100,000 Mukti Bahini guerrillas who knew the terrain intimately and enjoyed widespread support from a hostile local population of over 70 million. The Pakistani troops were spread thin across “fortress” defences in key towns, but rapid Indian advances bypassed these positions, encircling Dhaka in just 13 days of open war.

The 1970 Elections and the Refusal to Transfer Power: The Point of No Return

In the 1970 general elections—the first direct elections in Pakistan’s history—the Awami League, led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, secured a resounding victory in East Pakistan, winning 160 out of 162 allocated National Assembly seats (constituting an absolute majority of 167 out of 313 total seats in a united Pakistan). This landslide made Mujib constitutionally destined to become Prime Minister of the entire country, commanding a clear parliamentary mandate.

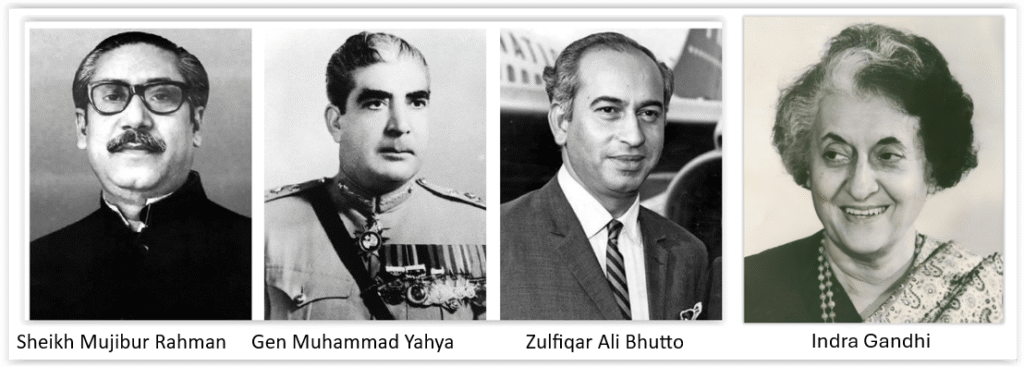

However, the military regime under General Yahya Khan refused to transfer power, delaying the National Assembly session amid political maneuvering. At the behest of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, leader of the Pakistan Peoples Party (which dominated West Pakistan but lacked a national majority), Mujib was portrayed as a separatist and traitor unwilling to compromise. Bhutto famously declared he would “break the legs” of anyone attending the assembly in Dhaka and insisted on power-sharing or separate rule, preferring to avoid opposition benches.

This impasse led to the launch of Operation Searchlight on March 25, 1971—a military crackdown to crush Bengali aspirations. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was arrested that night in Dhaka, declared a traitor, and secretly flown to West Pakistan, where he was imprisoned and later faced a closed-door military trial on charges of treason. This refusal to honor the electoral verdict proved catastrophic, igniting widespread resistance and setting the stage for the tragic events that followed.

India’s Role in the Disintegration: Strategic Planning and External Intervention

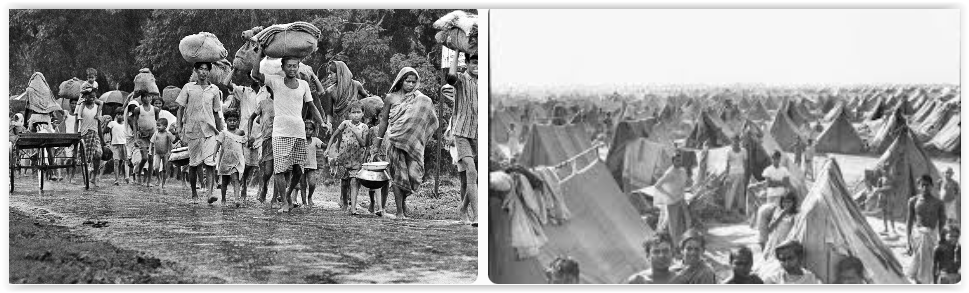

India’s involvement under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was a calculated strategy to exploit internal grievances and actively engineer the separation of East Pakistan. As early as April 1971, following the military crackdown, Gandhi’s cabinet directed the army to prepare for intervention, viewing war as preferable to indefinitely hosting millions of refugees. India provided extensive covert support to the Mukti Bahini guerrillas, including training camps, arms, funding, and logistical aid through Operation Jackpot, transforming them into an effective force that harassed Pakistani troops and controlled swathes of territory.

Ms. Indra Gandhi masterfully leveraged the refugee crisis—nearly 10 million Bengalis fleeing alleged atrocities—to pressure Pakistan economically and diplomatically. While India sheltered the refugees, it simultaneously used the humanitarian disaster to portray Pakistan as aggressor through aggressive media campaigns and personal diplomatic tours across Europe and the US, isolating Pakistan internationally and countering US support for Islamabad. This propaganda effort, amplified by reports of Pakistani military actions, shifted world opinion and neutralized potential UN interventions.

Ultimately, when guerrilla warfare alone proved insufficient, India launched a full-scale military offensive on December 3, 1971, after Pakistani pre-emptive strikes in the West. With superior numbers, air dominance, and Mukti Bahini coordination, Indian forces rapidly advanced, encircling Dhaka against an already exhausted, outnumbered, and isolated Pakistani garrison. Gandhi’s strategy culminated in the swift 13-day war, leading to the surrender and the creation of Bangladesh—a profound strategic victory for India that divided Pakistan in to 2 separate countries.

The Surrender: Expectations of Heroic Resistance vs. Harsh Reality

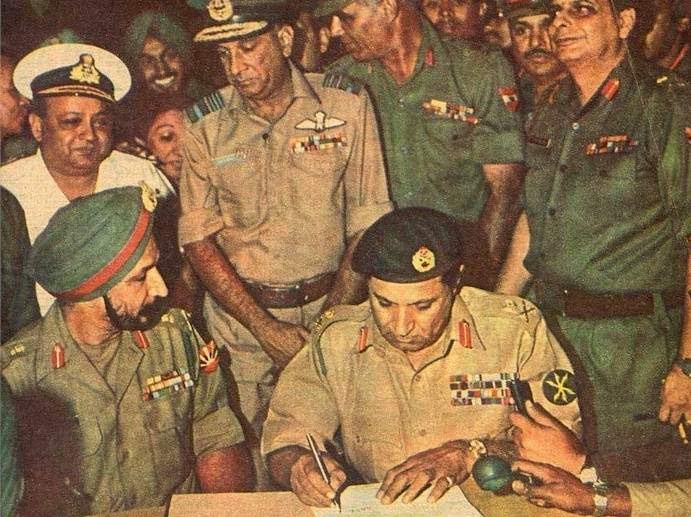

The surrender is deeply controversial and seen by many as avoidable or dishonorable. The Pakistani Army, steeped in a tradition of martial valor, was expected to fight to the bitter end—perishing in battle rather than accepting what was viewed as a humiliating capitulation. Lieutenant General AAK Niazi, Commander of the Eastern Command, faced intense criticism in Pakistan for signing the Instrument of Surrender at Dhaka on 16 December 1971.

The Hamoodur Rahman Commission, established to investigate the debacle, highlighted leadership failures, moral lapses, and strategic miscalculations but also noted the impossible situation: encirclement of Dhaka, collapsed supply lines, demoralized troops, and the risk of mass civilian and military casualties in continued urban fighting. Niazi argued he surrendered to prevent further bloodshed and potential massacre by hostile forces. However, many in Pakistan viewed it as a betrayal of the army’s ethos, expecting defiance even in hopelessness. This perception of “humiliating defeat” rather than a pragmatic ceasefire has lingered, fueling debates on honor, duty, and the cost of prolonged resistance in an untenable position.

Conclusion

The Fall of Dhaka was not inevitable from 1947 but resulted from unaddressed grievances, miscalculations, and external pressures. Reflecting on these factors—cultural imposition, economic inequity, political exclusion, security neglect, overwhelming numerical disparity, and the controversial surrender—offers lessons for unity in diverse nations. While perspectives differ, the tragedy underscores the cost of ignoring majority aspirations in a federation and the heavy burden of military decisions in asymmetric conflicts.

Reading this was deeply moving and painful at the same time. It brought back the weight of history, loss, and unanswered questions that still linger in our collective memory. Your words capture not just events, but the human suffering, betrayal, and silence that followed. This piece forces the reader to pause, reflect, and feel — something not many articles manage to do. Thank you for writing this with such honesty and courage.