(Quratulain Khalid)

India, a nation celebrated for its kaleidoscopic cultural diversity and religious pluralism, stands at a crossroads with the proposed Uniform Civil Code (UCC), a legislative ambition to standardise personal laws governing marriage, divorce, inheritance, adoption, and maintenance across all communities. Enshrined in Article 44 of the Indian Constitution as a Directive Principle of State Policy (DPSP), the UCC has been a contentious issue since India’s independence in 1947. Its recent enactment in Uttarakhand in 2024 and advocacy by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led states signal a renewed push, yet the proposal faces formidable challenges in India’s plural society. This article argues that the code threatens religious freedom, undermines cultural diversity, risks state overreach, and could deepen social polarisation, drawing on historical, legal, and governance perspectives to highlight why the UCC may falter in India’s complex social fabric.

I. Historical Context: Personal Laws and Pluralism in India

a. Colonial Legacy and Constitutional Debates

India’s personal laws have deep historical roots, shaped during the British Raj to govern Hindus, Muslims, Christians, Parsis, and other communities based on their religious customs. The Lex Loci Report of 1840 recommended codifying criminal laws but explicitly excluded personal laws to avoid antagonising religious leaders, a policy reinforced by the Queen’s Proclamation of 1859, which promised non-interference in religious matters. This approach entrenched a plural legal system, allowing communities to maintain distinct practices in marriage, inheritance, and family matters.

During the drafting of the Indian Constitution (1947–1950), luminaries like Jawaharlal Nehru and B.R. Ambedkar advocated for a UCC to promote national unity and gender equality. However, opposition from Muslim and Hindu representatives, wary of disrupting traditional practices, led to its inclusion as a non-enforceable DPSP under Article 44, which states, “The State shall endeavour to secure for the citizens a uniform civil code throughout the territory of India.” Article 37 clarifies that DPSPs are not legally binding, reflecting a compromise to respect India’s pluralism.

Post-independence, the Hindu Code Bills (1955–1956) codified Hindu personal laws, addressing marriage, succession, and guardianship for Hindus, Buddhists, Jains, and Sikhs, but left Muslim, Christian, and Parsi laws untouched. The Shah Bano case (1985), where the Supreme Court granted maintenance to a divorced Muslim woman under secular law, sparked nationwide debate, highlighting tensions between state intervention and religious autonomy. The subsequent Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act 1986, passed to appease conservative Muslim groups, underscored the delicate balance between secularism and religious freedom.

b. Goa as an Exception

Goa, governed by the Portuguese Civil Code of 1867, remains India’s only state with a form of UCC, mandating equal inheritance, monogamy, and compulsory marriage registration. However, its success owes to Goa’s unique historical and demographic context, with a smaller, less diverse population. Scaling this model to India’s 1.4 billion people, with myriad castes, sects, and regional traditions, is far from straightforward.

II. The UCC in Uttarakhand: A Contentious Precedent

On 7 February 2024, Uttarakhand became the first Indian state to enact a UCC Bill, passed by the BJP-led assembly and ratified by President Droupadi Murmu on 13 March 2024. The law standardises marriage age (18 for women, 21 for men), bans polygamy, mandates marriage and live-in relationship registration, and ensures equal inheritance for sons and daughters. Chief Minister Pushkar Singh Dhami hailed it as a step towards “equality and uniformity,” particularly for women’s rights. However, the law exempts Scheduled Tribes, acknowledging their distinct customs under the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution.

Critics, including opposition parties like the Congress and women’s rights activists, argue the bill was rushed for electoral gains ahead of the 2024 Lok Sabha elections, bypassing thorough public consultation. The mandatory registration of live-in relationships, with penalties of up to three months’ imprisonment or a Rs 25,000 fine, raises fears of state surveillance and moral policing, particularly targeting minority and marginalised communities. Petitions challenging the law’s constitutionality have been filed, citing potential violations of Article 25 (freedom of religion) and Article 21 (right to privacy).

III. Legal and Constitutional Challenges

a. Article 44 vs. Religious Freedom

Article 44’s call for a UCC conflicts with Articles 25–28, which guarantee freedom of religion, including the right to practice and manage religious affairs. Critics argue that imposing a UCC could infringe on these fundamental rights, particularly for Muslims, whose Sharia-based personal laws govern marriage, divorce, and inheritance. The 2018 Law Commission Report, led by Justice Balbir Singh Chauhan, concluded that a UCC is “neither necessary nor desirable,” advocating instead for reforms within existing personal laws to address discrimination.

The Supreme Court has issued mixed signals. Cases like Sarla Mudgal (1995), Lily Thomas (2000), and Shayara Bano (2017) urged a UCC to promote gender justice and national unity, yet the court has also recognised India’s pluralism. In Pannalal Bansilal Pitti (1996), it advocated a gradual approach, warning against abrupt imposition. Legal scholars argue that state-level UCCs, as seen in Uttarakhand, may violate Article 245, which limits states’ legislative authority to their territories, potentially creating legal inconsistencies across India.

b. Federalism at Stake

Personal laws fall under the Concurrent List, allowing both Parliament and state legislatures to legislate. However, a national UCC requires Parliamentary approval with a two-thirds majority to amend the Constitution, a threshold unmet in the 18th Lok Sabha after the BJP’s National Democratic Alliance (NDA) lost its supermajority in 2024. State-level UCCs risk fragmenting the legal framework, undermining the uniformity envisioned by Article 44. Opposition-ruled states like Kerala and West Bengal have rejected the UCC, with Kerala’s 2023 resolution criticising its lack of inclusivity.

IV. Social and Cultural Concerns

a. Threat to Religious Diversity

India’s plural society, encompassing Hindus, Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Jains, Buddhists, Parsis, Jews, and tribal communities, thrives on its cultural diversity. Personal laws reflect this mosaic, accommodating practices like the Khasi tribe’s matrilineal inheritance in Meghalaya or Muslim polygamy under the Shariat Application Act 1937. A UCC risks cultural homogenisation, eroding traditions integral to community identities. For instance, Muslim organisations like the Indian Union Muslim League (IUML) argue that banning polygamy or triple talaq (already criminalised in 2019) targets Muslim practices while ignoring similar customs among Adivasi or Hindu communities.

b. Minority Anxieties

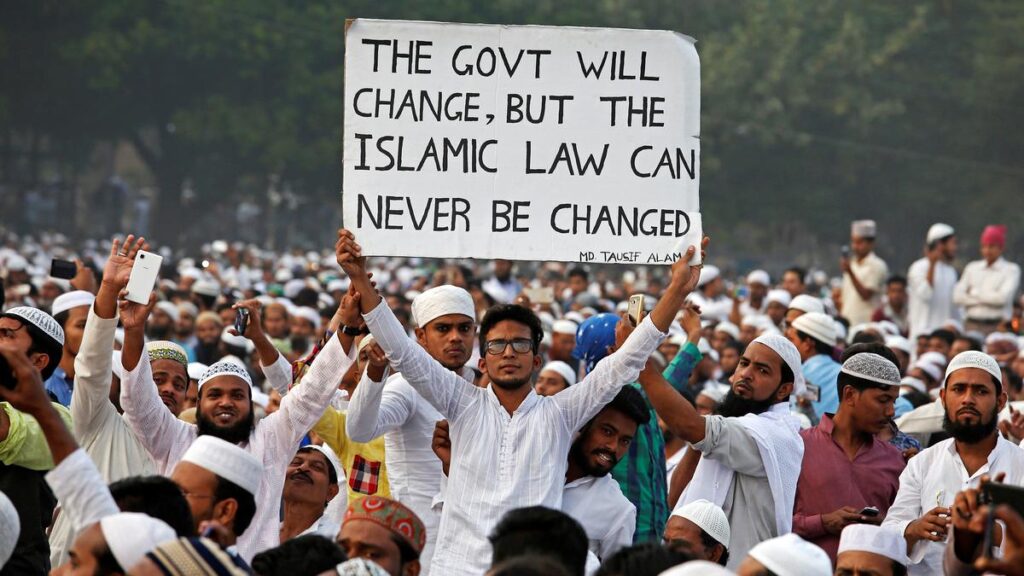

Muslims, comprising 14% of India’s population, fear the UCC is a BJP strategy to marginalise them. The party’s rhetoric, framing Muslim personal laws as “regressive,” reinforces stereotypes, as noted by activists like Adv Dr Shalu Nigam. The US Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) has flagged India’s minority rights record, citing the UCC as a potential tool for discrimination. Tribal communities in Nagaland, Meghalaya, and Mizoram oppose the UCC, fearing erosion of Sixth Schedule protections. In Nagaland, civil society groups threatened to burn legislators’ homes if the UCC is imposed, highlighting deep resistance.

c. Gender Justice or Political Motive?

Proponents claim the UCC advances gender equality, citing discriminatory practices like unequal inheritance in Muslim law or Hindu joint family systems. However, critics argue that the BJP’s selective focus on Muslim practices, while exempting tribal customs, betrays political motives. The Hindu Succession Act 2005 already grants Hindu women equal inheritance rights, suggesting that targeted reforms, not a blanket UCC, could address gender disparities. Kadeeja Mumthaz, a Muslim scholar, advocates amending personal laws to ensure equity without imposing uniformity.

V. Political Polarisation and State Overreach

a. BJP’s Electoral Strategy

The BJP has championed the UCC since its 1998 and 2019 election manifestos, alongside Ayodhya and Kashmir issues. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s June 2023 call for a UCC, echoed in 2025, frames it as essential for a “modern nation.” However, opposition parties, including Congress, Trinamool Congress (TMC), and Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), label it a “diversionary tactic” to polarise voters before elections. The BJP’s loss of a two-thirds majority in 2024 complicates national implementation, pushing states like Gujarat, Assam, and Uttar Pradesh to draft their own UCCs, risking legal fragmentation.

b. Risks of Surveillance and Control

The Uttarakhand UCC’s requirement to register live-in relationships raises alarms about state overreach. Critics fear it enables surveillance of personal lives, particularly for interfaith couples or minorities, already targeted by anti-conversion laws in BJP-ruled states. The Nagaland Transparency, Public Rights Advocacy and Direct-Action Organisation warned that such measures could erode tribal autonomy, while Muslim activists see it as a pretext to monitor their communities.

VI. Regional Echoes: Lessons from Pakistan

India’s UCC debate resonates with Pakistan’s struggles over personal law reforms. The Islamabad Capital Territory Child Marriage Restraint Act 2025, banning marriages under 18, faced opposition from the Council of Islamic Ideology and conservative parties, mirroring India’s tensions between reform and religious tradition. In both nations, personal laws are battlegrounds where religion, politics, and rights collide. Pakistan’s challenges highlight that imposing uniform laws without consensus risks alienating communities, a cautionary tale for India.

VII. The Case Against the UCC

a. Undermining Secularism

India’s secularism, defined as equality of all religions rather than Western-style separation of state and religion, accommodates plural legal systems. The 2018 Law Commission argued that personal law reforms, not a UCC, better balance equality and diversity. A UCC risks imposing a majoritarian framework, alienating minorities and contradicting Article 25.

b. Eroding Democratic Trust

The BJP’s push for the UCC, without a public draft or inclusive consultation, undermines democratic processes. The 22nd Law Commission’s 2023 call for public input was limited to 30 days, insufficient for a nation of India’s diversity. Kerala’s rejection and Northeast opposition reflect a lack of consensus, risking communal tensions.

c. Alternative Approaches

Rather than a one-size-fits-all UCC, India could:

- Reform Personal Laws: Amend discriminatory provisions, as in the Hindu Succession Act 2005 or Triple Talaq ban (2019), to ensure gender justice without erasing cultural identities.

- Promote Secular Options: Strengthen the Special Marriage Act 1954, allowing couples to opt for secular laws without mandating uniformity.

- Engage Communities: Conduct nationwide consultations with religious leaders, legal experts, and civil society, as advocated by the 2018 Law Commission.

VIII. Conclusion

The Uniform Civil Code, while promising legal clarity and gender equality, threatens India’s pluralistic fabric. Its imposition risks infringing religious freedom, eroding cultural diversity, and deepening social divides, particularly for Muslims and tribal communities. The Uttarakhand UCC, with its surveillance mechanisms, exemplifies state overreach, while the BJP’s electoral motives cast doubt on its sincerity. India’s history of accommodating diversity, from the British Raj to the Constitution, suggests that plural legal systems are not a weakness but a strength. A just legal framework must empower communities to choose, not impose uniformity at the cost of trust. Without inclusivity, the UCC risks becoming a symbol of division, undermining India’s secular and democratic ethos.