(By Khalid Masood)

Rare earth elements (REEs), a group of 17 chemically similar metals including neodymium, dysprosium, and lanthanum, are pivotal to the global high-tech, green energy, and defence sectors. From smartphones and electric vehicle (EV) batteries to wind turbines and precision-guided missiles, these minerals underpin modern technology and the transition to a low-carbon economy. Pakistan, with its mineral-rich regions in Balochistan, Gilgit-Baltistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK), holds significant but untapped REE potential. However, challenges such as insurgency, inadequate infrastructure, and a lack of refining technology hinder its ability to emerge as a global player. This article explores Pakistan’s REE reserves, the global supply chain dynamics, and the geopolitical, economic, and environmental implications for the country, drawing on archaeological and geological insights to contextualise its prospects.

I. Understanding Rare Earth Elements and Their Global Significance

a. What Are REEs?

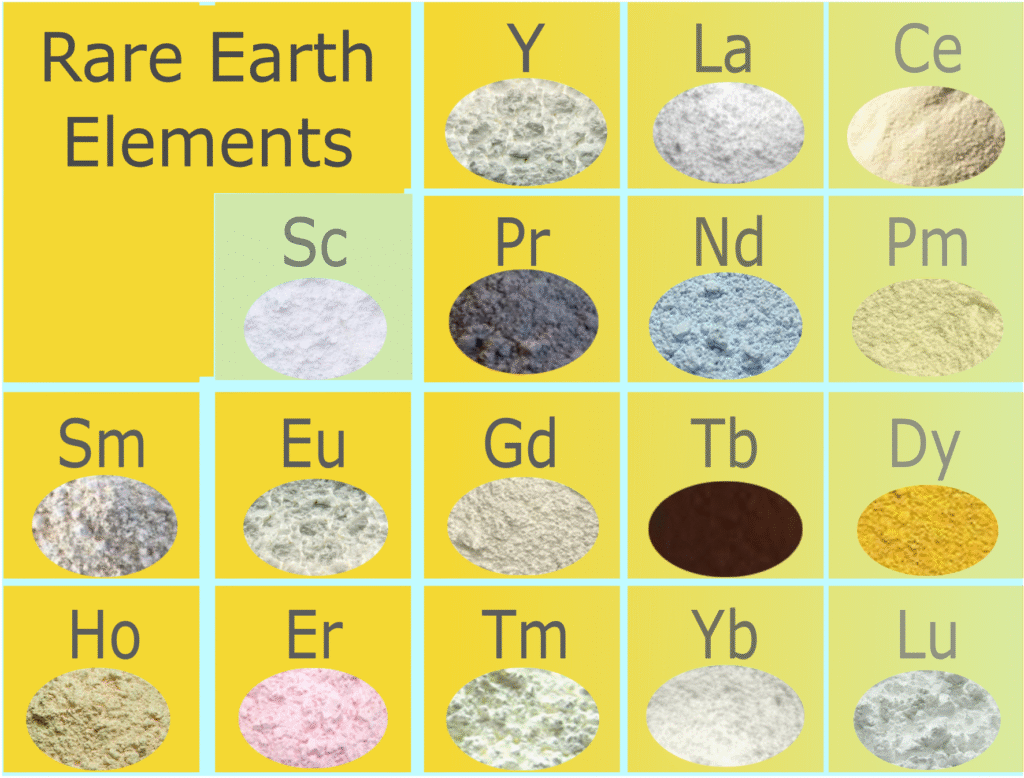

REEs comprise 15 lanthanides, plus scandium and yttrium, valued for their unique magnetic, luminescent, and catalytic properties. These elements are critical for:

- High-Tech Industry: Neodymium and praseodymium are essential for permanent magnets in hard drives, smartphones, and data centre servers supporting artificial intelligence (AI).

- Green Technology: EV batteries require 70 to 100 kg of REEs per vehicle, while a 1 MW wind turbine needs 200 to 300 kg of REE magnets.

- Defence Applications: F-35 fighter jets use 420 kg of REEs for radar, avionics, and propulsion systems.

The supply chain involves mining, separation, refining, manufacturing, and recycling. Separation and refining are particularly complex, requiring advanced chemical processes to isolate individual REEs from ore due to their chemical similarity. These processes generate toxic waste and radioactive byproducts, posing significant environmental challenges.

b. Global Supply Chain Dynamics

China dominates the REE market, controlling 60% of global mining and 90% of refining capacity as of 2023. Other players include:

- Mining: Australia (Lynas Corporation), the United States (MP Materials), Vietnam, and Russia.

- Reserves: Vietnam (22 million tonnes), Brazil (21 million tonnes), and Russia (12 million tonnes) hold significant deposits, but extraction lags due to technical and financial constraints.

- Refining: China’s near-monopoly on refining limits global diversification, with Australia and the United States investing heavily to close the gap.

Demand is surging due to the energy transition, defence needs, and technological growth. The International Energy Agency (IEA) projects global REE demand to triple by 2035, driven by EVs, renewables, and AI infrastructure. China has leveraged its dominance through export quotas (e.g., gallium and germanium restrictions in 2023) and bans on REE processing technology exports (December 2023), heightening geopolitical tensions.

II. Pakistan’s REE Potential: A Geological and Archaeological Perspective

a. Geological Context

Pakistan’s geological diversity, shaped by its position at the convergence of the Indian, Eurasian, and Arabian tectonic plates, fosters rich mineral deposits. The Chagai Arc in Balochistan, part of the Tethyan Metallogenic Belt, is renowned for copper and gold at Reko Diq and Saindak, with preliminary surveys indicating REE presence, including bastnäsite and monazite. In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, areas like Chitral and Malakand show traces of REEs in igneous and metamorphic rocks, while Gilgit-Baltistan hosts REE-bearing minerals in Skardu and Astore. Estimates suggest Pakistan’s mineral wealth, including REEs, could be worth $6 to $50 trillion, with Balochistan alone holding 12 of the 17 REEs.

Archaeologically, Balochistan’s mineral-rich regions have historical significance. Ancient mining sites in Chagai and Lasbela, dating back to the Indus Valley Civilisation (2600–1900 BCE), reveal early exploitation of copper and semi-precious stones, suggesting a long-standing human interaction with the region’s geology. These sites, studied through archaeometallurgy, indicate traditional knowledge that could inform modern exploration techniques.

b. Current Status

Pakistan has no commercial REE mining or refining operations. Geological surveys remain incomplete, with exploration described as “unscientific” and “sketchy” due to limited funding and expertise. Key projects like Reko Diq (5.9 billion tonnes of copper-gold ore) and Saindak (producing 15,800 tonnes of copper, 1.5 tonnes of gold, and 2.8 tonnes of silver annually) focus on conventional minerals, not REEs. The absence of REE-specific infrastructure and technical expertise hampers progress.

III. Opportunities for Pakistan in the REE Market

a. Economic Potential

Developing REE resources could transform Pakistan’s economy:

- Revenue Generation: Reko Diq is projected to generate $74 billion in free cash flow over 37 years, with potential REE extraction adding further value.

- Job Creation: Reko Diq alone expects to create 7,500 construction jobs and 4,000 permanent roles, with REE projects offering similar prospects if developed.

- Export Diversification: REEs could reduce reliance on textile exports, positioning Pakistan as a niche supplier in global supply chains.

b. CPEC Infrastructure

The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) provides roads, ports, and power grids that could support REE mining. Gwadar Port, a key CPEC node, offers a strategic export route to China and global markets. China’s expertise in REE refining could facilitate joint ventures, though this risks deepening Pakistan’s dependence on Beijing.

c. Foreign Investment

The Pakistan Minerals Investment Forum 2025 highlighted interest from Saudi Arabia, Canada, and the United States. Barrick Gold’s $5.5 billion investment in Reko Diq and Saudi Arabia’s potential 15% stake signal growing confidence, which could extend to REE exploration. US interest, spurred by China’s export restrictions, positions Pakistan as a potential alternative supplier.

IV. Challenges to Pakistan’s REE Ambitions

a. Baloch Insurgency

Balochistan, home to most of Pakistan’s REE deposits, is plagued by the Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA) insurgency. The BLA opposes foreign investment, viewing it as exploitation. Notable incidents include:

- July 2025: Nine Punjabi civilians killed on the N70 highway in Zhob.

- March 2025: Jaffar Express hijacking, resulting in 33 deaths.

- November 2024: Quetta railway station bombing, killing 32.

These attacks target CPEC projects and mining operations, deterring investors. The Pakistan Army’s pledge for “robust security” has yet to fully stabilise the region.

b. Technological and Infrastructural Gaps

REE extraction requires advanced solvent extraction and hydrometallurgical processes, which Pakistan lacks. China’s ban on REE processing technology exports limits access to expertise. Refining facilities are absent, and existing infrastructure (e.g., Saindak) is outdated, producing only copper blister rather than refined REEs. Water scarcity, critical for mining, exacerbates challenges, with Balochistan’s operations potentially consuming 40% of local water resources.

c. Environmental and Regulatory Issues

REE mining generates toxic waste and radioactive tailings, as seen in Saindak’s groundwater pollution. Pakistan’s environmental regulations are underdeveloped, lacking frameworks for sustainable mining like those in Sweden or Canada. The Balochistan Mines and Minerals Act 2025, passed with minimal debate, prioritises federal control over provincial autonomy, sidelining local communities and fueling resentment.

d. Geopolitical Tensions

China’s $60 billion CPEC investment ties Pakistan to Beijing, complicating partnerships with the US and EU, who seek to reduce China’s REE dominance. India’s alleged support for Baloch separatists, though unproven, adds further complexity. Pakistan’s economic crisis and $130 billion external debt (much owed to China) limit its ability to independently fund REE development.

V. Geopolitical Implications and Strategic Options

a. Global REE Race

The US and EU are countering China’s dominance through:

- US Investments: $35 million to MP Materials and Defense Production Act support for domestic mining.

- EU Initiatives: The Critical Raw Materials Act 2023 targets 10% domestic mining by 2030.

- Alliances: The Minerals Security Partnership (13 nations) aims to diversify supply chains.

Pakistan’s REE reserves position it as a potential partner, but its alignment with China via CPEC raises concerns for Western investors.

b. Strategic Outlook for Pakistan

Pakistan could:

- Partner with China: Leverage CPEC and Chinese expertise to develop REE mining, but risk over-dependence and debt traps.

- Engage the US/EU: Offer raw ore to Western markets, though security risks and lack of refining capacity make this unlikely before 2040.

- Develop Domestic Capacity: Invest in geological surveys, technical training, and green mining to build a self-sufficient REE industry, requiring decades and billions in investment.

VI. Recommendations for Pakistan

- Geological Mapping: Conduct comprehensive surveys in Balochistan, KPK, and Gilgit-Baltistan using modern geophysical techniques to verify REE deposits.

- Security Enhancements: Deploy drones (Shahpar III) and rapid-response units to secure mining zones, while engaging Baloch communities to reduce insurgency.

- Environmental Standards: Adopt Swedish/Canadian green mining models to minimise ecological damage and ensure community benefits.

- Technical Development: Partner with Australia or Canada for REE refining expertise, bypassing China’s export restrictions.

- Local Empowerment: Ensure Balochistan receives equitable royalties (e.g., 25% stake in Reko Diq) and invest in healthcare, education, and water infrastructure to address grievances.

- Diplomatic Balancing: Maintain neutrality in the US-China rivalry, attracting investment from both while prioritising national interests.

VII. Conclusion

Rare earth elements are the backbone of the digital and green economies, making their supply chains a geopolitical battleground. Pakistan’s REE potential in Balochistan, KPK, and Gilgit-Baltistan offers a transformative opportunity, but insurgency, technological gaps, and environmental challenges pose formidable barriers. The CPEC provides a foundation for infrastructure, but China’s dominance risks entrenching dependency. Engaging US and EU partners requires overcoming security and regulatory hurdles. By investing in geological exploration, sustainable mining, and local empowerment, Pakistan could position itself as a niche supplier in the global REE market. However, without decisive action, its mineral wealth risks remaining a tantalising but unrealised promise, leaving Pakistan on the sidelines of the new Great Game.